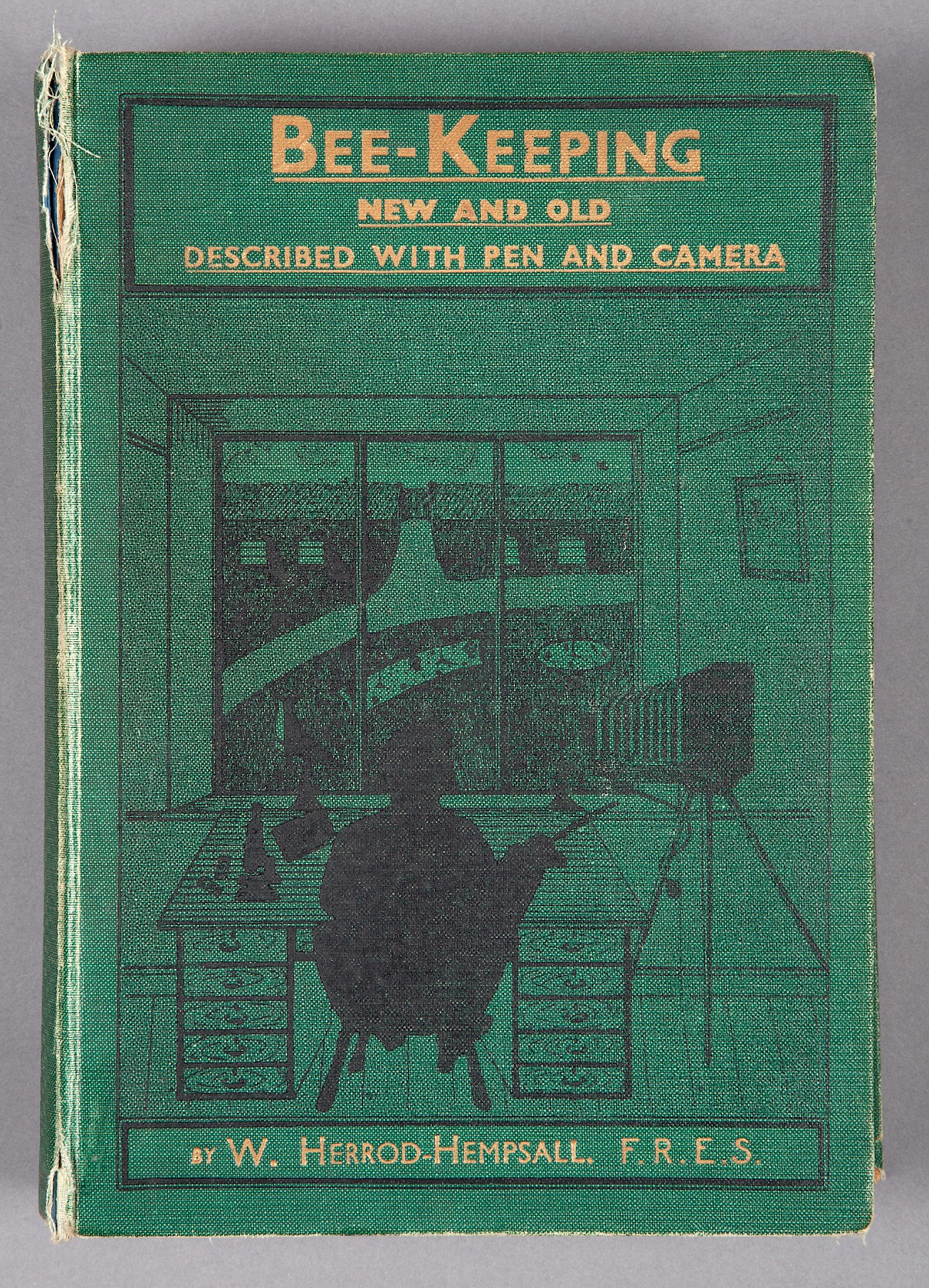

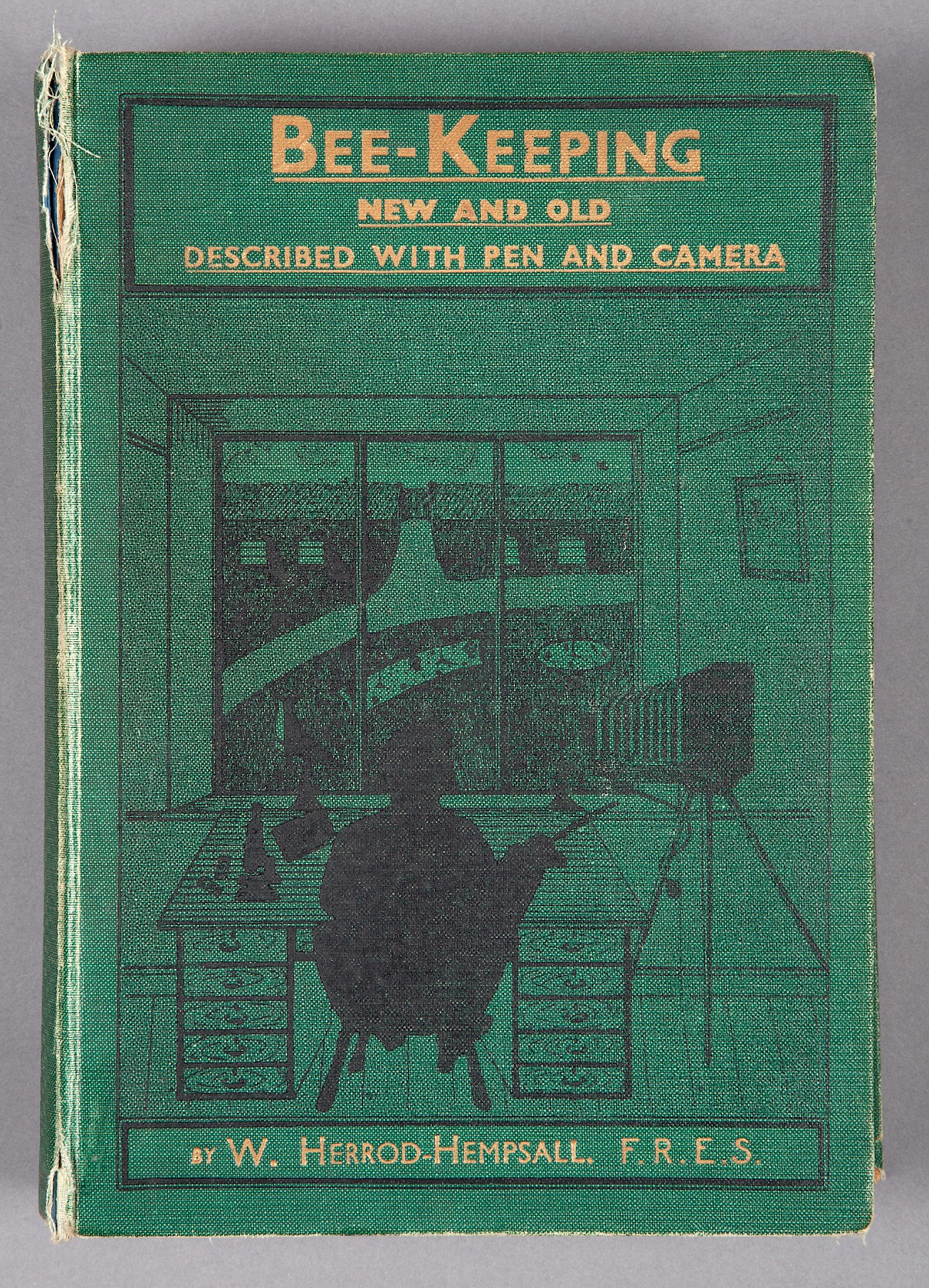

William Herrod-Hempsall, Bee-Keeping new and old: described with pen and camera (London: The British Bee Journal, 1930)

The Ministry of Bees is responsible for the relationship between humans and all bee species. It is tasked by bees to safeguard the history of this age-old relationship, and does so by producing polymorphous ethnographies. These ethnographies combine various media, including video, sound, photography, and writing in order to represent the world of bees to humans and promote Socialist Beekeeping practices. The Ministry aims to establish a framework for the future of this relationship in the context of climate breakdown – a future free from extractive practices and grounded in ancestral knowledge.

In the face of our political institutions failing to take concrete action towards the decline of bees and other insect populations worldwide (1), I decided to create Apian, a self-proclaimed Ministry of Bees, in 2014. I borrowed apian from Juan Antonio Ramirez, who used it extensively in his essay The Beehive Metaphor (2000). Apian is an adjective that defines something which relates to the world of bees – from architecture to behaviour, basically as broad as one’s imagination can be. The addition of the Ministry of Bees came a bit later and was motivated by the ideas behind the word ministry itself.(2) Connoting power, a ministry is a governmental institution that could, in theory, change something. To me, it seemed more feasible to act under a Ministry rather than a studio. Of course, this is a semantic dispute, but words matter. So to be clear, Apian does not aim to be a metaphorical entity – quite the contrary. It rather aims to fight for the material condition of this age-old relationship, strengthening it in collaboration with bees, beekeepers and other bee lovers.

Taking matters into its own hands, the Ministry of Bees is responsible for the relationship between humans and all bee species.(3) It is tasked by bees to safeguard the history of this age-old relationship, and does so by producing polymorphous ethnographies. These ethnographies combine various media, including video, sound, photography, and writing, in order to represent the world of bees to humans and promote Socialist Beekeeping practices. The Ministry aims to establish a framework for the present and future of this relationship in the context of climate breakdown – a future free from extractive practices and grounded in ancestral knowledge.

So far, the Ministry’s research has primarily focused on Western Europe.(4) However, this focus does not mean that it aims to be Eurocentric. It is first a conscious decision to avoid perpetuating anthropological colonial legacies, and instead imagine non-extractive forms of producing knowledge, especially when it comes to working away from home. Non-Eurocentric knowledge aims to be gathered by inviting like-minded bee lovers to contribute to, or join, the Ministry, rather than extracting it myself. This special issue is thus a call for exactly that – to invite colleagues from around the planet to collaborate and work with the Ministry. Join us! We demand ethical futures for bees and humans all over the planet. Socialist Beekeeping now!

Whereas Apian was founded and is still mainly operated by me, Aladin Borioli, the use of an alias aims to reveal the Ministry’s inherent collaborative face and encourage future exchange. As I said above, I didn’t want to create a studio; Apian is in the process of becoming an institution, which ultimately aims to function without me. However, I wanted to give a brief introduction of myself here as the Ministry draws from personal and tangible experiences. I was born and raised in the French-speaking countryside of Switzerland in the late ’80s. I learnt beekeeping from my grandfather as a teenager (fig. i). Since then, I’ve continued to keep bees out of passion (yes, I do love bees) (5) and as a research method. Meanwhile, I have a background in visual communication (graphic design and photography), anthropology, and bits and bobs of knowledge in critical philosophy. Today, as a visual anthropologist, artist, and beekeeper, I work as a minister for the Ministry of Bees.

Drawing from this background, the Ministry uses an odd kit of methods which mixes an anthropological approach – tainted by philosophical inputs – with the practice of art and beekeeping. Concretely, that means conducting interviews with beekeepers, bee scholars, and artists – basically anyone with shared sensibilities towards bees. The Ministry also uses methods such as participant observation, elicitation sessions, and collaborative workshops. At the heart of the Ministry’s methods is a form of collaborative ethnography.(6) Collaborative ethnography transforms fieldwork into a space of co-imagination, allowing for the co-production of knowledge, bridging the gap between academic research and lived experience.

Meanwhile, each encounter is also an invitation to join the Ministry, as an attempt to go beyond collaboration. Rather than studying communities, the Ministry aims to build a community itself – a planetary socialist hive. So far, it has worked with a range of friends and colleagues, including academics, beekeepers, artists, and activists. I’ll mention just a few: the visual anthropologist Ellen Lapper; the musician and artist Laurent Güdel; the bee-scholars Dorothea Brückner, Randolf Menzel, and Nicolas Césard; the artist and graphic designer Nicolas Polli, who also co-publishes Apian Gazette via Ciao Press; and, of course, thousands of bees (even though the collaboration with bees is pretty asymmetrical, to say the least).

When it comes to its economy, a bit like its methods, The Ministry has been built from various pots of money. A large chunk has come from artistic grants; again, to only mention a few, the Ministry has been supported by Pro Helvetia, La Becque, EyeBeam, Images Vevey, C/O Berlin, The CAIRN, Salt Gallery, and more. Alongside this, personal investments (side jobs and savings) and academic support (currently by the University of Amsterdam via a PhD position) continue to fund various activities and projects. Most of the money generated by exhibitions, selling publications, and so on, circulates back into the Ministry’s economy – when it’s not being used to pay my rent.

The polymorphous ethnographies produced by the Ministry are at the same time autonomous and related to one another. Each ethnography works as a research unit tackling a specific question. Once reunited, these ethnographies assemble a narrative universe which explores The Ministry’s meta question: the age-old human-bee relationship. Here I aim to outline a few of these ethnographies, offering an overview of The Ministry’s activities over the past ten years.

I want to start with Hives, 2400 B.C.E. – 1852 C.E – a visual history of the beehive. In 1852, the modern beehive was patented. Its subsequent success largely eliminated diversity in beehive design and led to the obsolescence of a varied history of alternative beekeeping techniques. While this is not Apian’s first work, it is a clear example of the Ministry’s approach. Through an array of archival images and an essay co-written with Ellen Lapper, this visual ethnography uncovers that forgotten history, offering a renewed perspective that challenges conventional historical linear narratives, creating a common ground for future beehive research.

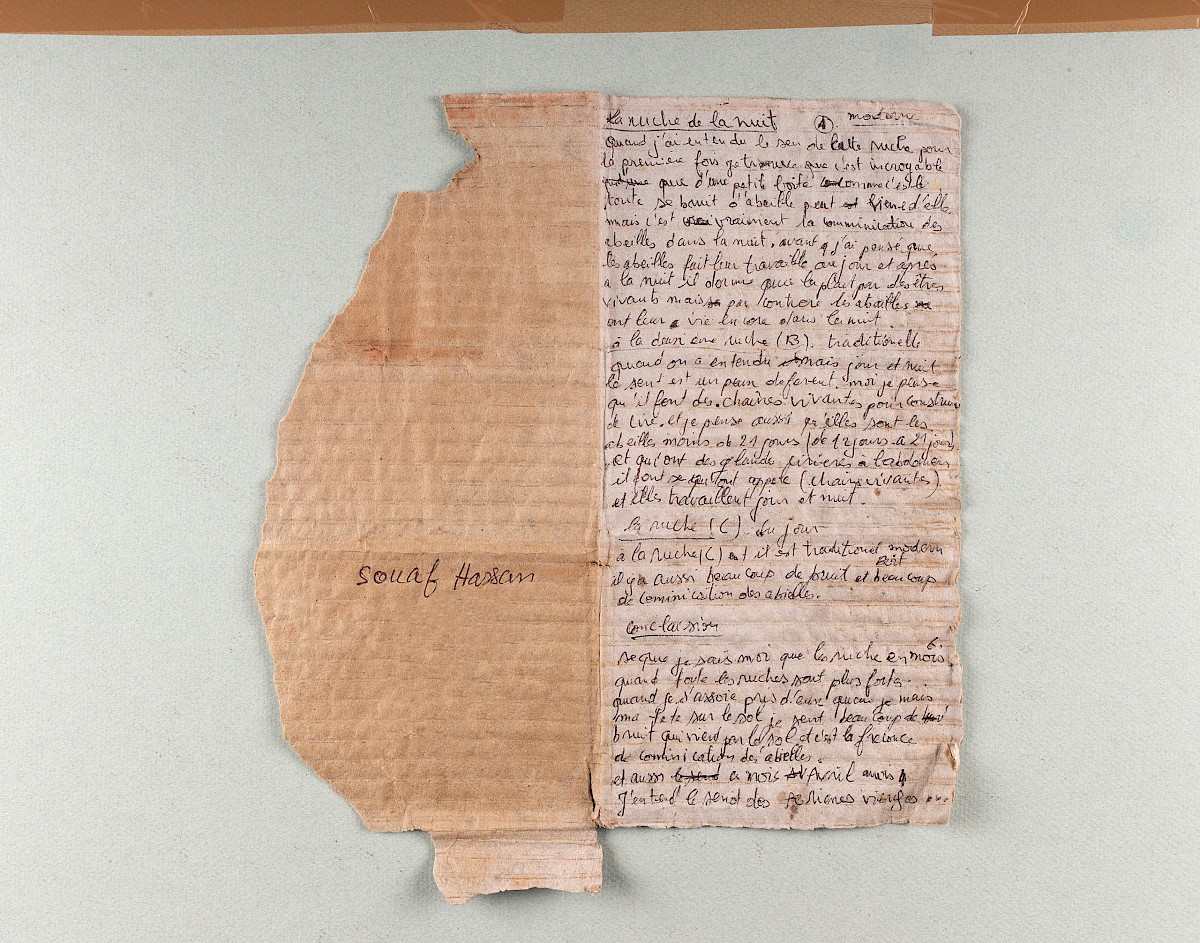

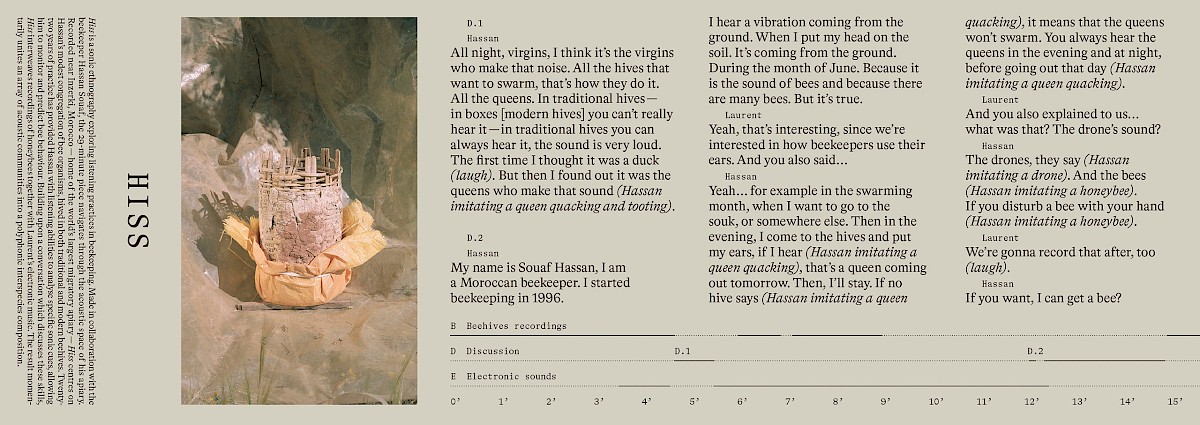

Taking a path towards sound, another example of the Ministry’s outputs is Hiss – a sonic ethnography which looks into listening practices in beekeeping. Made in collaboration with the Moroccan beekeeper Souaf Hassan and the Swiss musician Laurent Güdel, the twenty-nine-minute piece navigates through the acoustic space of Hassan’s apiary. Recorded near Inzerki, Morocco – home of the world’s largest migratory apiary – Hiss centres on Hassan’s modest congregation of bee organisms, hived in both traditional and modern beehives. Twenty-two years of practice has provided Hassan with listening abilities to analyse specific sonic cues, allowing him to monitor and predict bee behaviour. Building upon a conversation which discusses these skills, Hiss interweaves recordings of honeybees with Güdel’s electronic music. The result momentarily unites an array of acoustic communities into a polyphonic interspecies composition.

Moving now to the Internet, the Intimacy Machine (www.intimacy-machine.net) is an online DIY academic journal publishing research on all bee species worldwide. Contrary to conventional bee journals, the Intimacy Machine focuses on multimodal knowledge and alternative forms of knowledge distribution and production. Made of multiple layers, the platform – designed in collaboration with Studio Harris Blondman – shapes the visitor’s epistemic encounter with bees, starting with the multimodal content, followed by a summary of the original articles, and links to their sources. By shedding new light on existing research through its focus on the multimodality of knowledge, the Intimacy Machine brings academic bee research to a broader audience.

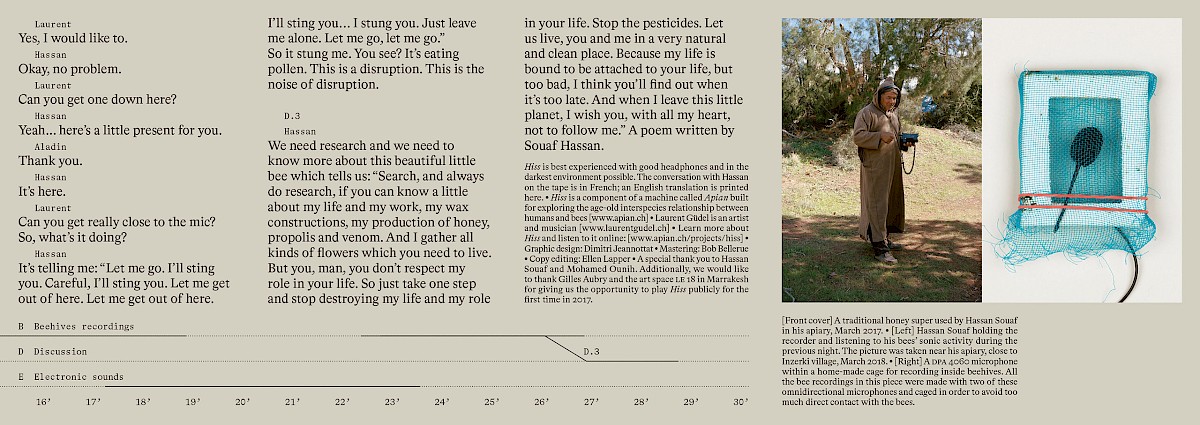

Films are also a central part of the Ministry’s productions. CH05 Drugs, for example, illustrates the data from an academic research study on the effect of prolonged exposure to non-lethal doses of neonicotinoid pesticides on honeybees.(7) Such pesticides kill insects deemed harmful by targeting their nervous systems. And while this study only focuses on honeybees, it is essential to stress that these chemicals have similar effects on a wide range of insects – including bumblebees, solitary bees, and other pollinators. Using a 3D model created by Nephilia, the film translates the study’s result into moving images, reaching an audience beyond academic walls.

Evident in Hives and the Intimacy Machine’s work, the Ministry has caught the so-called archive fever, an approach which culminates in Apian Index – the Ministry’s hidden archive. Built as part of Apian’s website, Apian Index regroups all the material gathered and produced by Apian. In short, it’s the Ministry’s data set and source of inspiration (hit key i, it’s not that well hidden).

So far, the Ministry has primarily focused on the common honeybee, but it is ultimately responsible for all bee species. Whereas honeybees are also at risk, they are being well looked after through the love of many keepers around the world. However, this isn’t the case for all bee species. The threats our bees are facing in apiaries – the impact of pesticides and especially, neonicotinoids, the spread of various diseases (Varroa mites amongst others), and the destruction of food sources and habitats – are exacerbated when it comes to wild and solitary bees. Let’s be clear: we know the origin of these threats. They stem directly from the extractive and destructive processes brought by capitalism, and the only option is to end this system as soon as possible.

In this context, Apian’s mission is to think about alternative beekeeping practices in alliance with bees and other bee lovers – an approach the Ministry calls Socialist Beekeeping. Socialist Beekeeping practices centre all bee species, while situating beekeeping within the context (local and global) it is practised. Global contexts such as climate breakdown caused by fosil capital, fascists seizing power, genocides and other ongoing deadly politics cannot be ignored. And while keeping bees can be a form of resistance in specific contexts, for example in the Palestinian Occupied Territories (8), how and where we do it matters. At the same time, beekeeping demands technodiversity and localised practices; different climates and political systems create varied practices. Socialist Beekeeping is thus situated, internationalist, and ethical, putting all bees at the forefront of its practices.(10)

Join us! To get in touch, please email: aladin@apian.ch

regroups all the material gathered and produced by Apian. In short, it’s Apian’s data set. You can search items via IDs, keywords, and so on, or randomly scroll the archive.

ID

↓

Titre

↓

Date

↓

Image

Type(s)

Mot(s) clé(s)

Archivé

↓

William Herrod-Hempsall, Bee-Keeping new and old: described with pen and camera (London: The British Bee Journal, 1930)

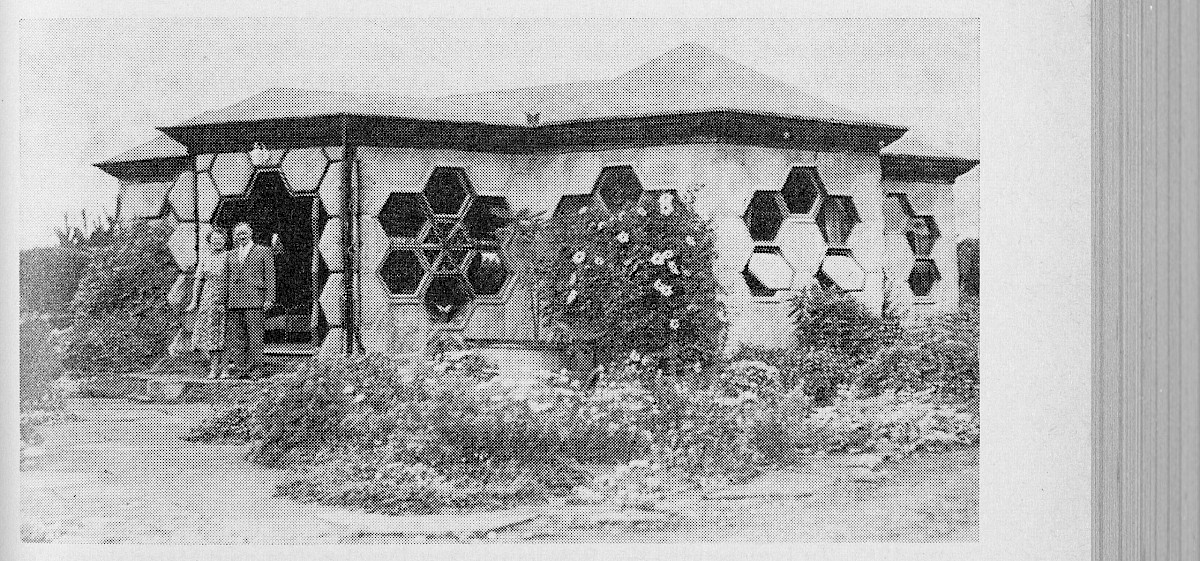

Beekeeper’s home in New Plymouth (New Zealand). Source: Schweizerische Bienen-Zeitung, no. 5 (May 1970)

“We need the research and we need to know more about this beautiful little bee which tells us: ‘Search and always do research if you can know a little about my life and my work, my wax constructions, my production of honey, propolis and venom. And I gather all kinds of flowers, fruits, which you need to live. But you, man, you don’t respect my role in your life. So just take one step and stop destroying my life and my role in your life. Stop the pesticides. Let us live you and me in a very natural and clean place. Because my life is bound to be attached to your life, but too bad, I think you’ll find out when it’s too late. And when I leave this little planet, I wish you, with all my heart, not to follow me.’”

A poem written by Souaf Hassan, Inzerki, Morocco, 2018.

Swarming of Bees, Reference Book 206. Ministry of Agriculture, Fisheries and Food. (London: Her Majesty’s Stationery Office, 1975 [1970]) Printed in Scotland at HMSO Press, Edinburgh.

Softcover, pp.23. Size: 15.1 (W) × 24.2 cm (H).

ISBN 0 11 240506 1

Contents (index)

Eva Crane, A Book of Honey (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1980)

Softcover, pp.193 with black and white illustrations. Size: 17 (W) × 24.3 cm (H).

ISBN 0 19 286010 0

“Honey is a splendid, entirely natural food, which has been treasured by people the world over from earliest times. Its production does not impoverish the environment, but actually enriches it, as bees pollinate the flowers they visit. Today honey is a commodity with an annual production of 800,000 tons, but it is only recently that research has shown how bees locate flowers containing nectar, and produce honey.

The book opens with a clear exposition of the amazing instinctive behaviour of bees, and of the composition and properties of honey. The use of honey in the home is discussed: as a gastronomic delicacy (and the author provides mouth-watering recipes, some new, some several thousand years old); as a remedy (for such ailments as hay fever and hangovers); and as a constituent of cosmetics. Dr. Crane goes on to tell the fascinating story of honey, from times before prehistoric man to the present day, and to show how bees have figured in the minds of men as magical or scared creatures. Numerous literary references show the value accorded to bees through the ages, as agents of industry and thrift, and as objects of superstitious belief. The hive is considered, too, as a political symbol.

Dr. Eva Crane began keeping bees in 1942 when she was given a swarm as a wedding present. She is now Director of the International Bee Research Association and travels widely to lecture and to study bees and honey.”

Blurb from the back cover.

Hiss is a sonic ethnography exploring listening practices in beekeeping. Made in collaboration with the beekeeper Souaf Hassan, the 29-minute piece navigates through the acoustic space of his apiary. Recorded near Inzerki, Morocco – home of the world’s largest migratory apiary – Hiss centres on Hassan’s modest congregation of bee organisms, hived in both traditional and modern beehives. Twenty-two years of practice has provided Hassan with listening abilities to analyse specific sonic cues, allowing him to monitor and predict bee behaviour. Building upon a conversation which discusses these skills, Hiss interweaves recordings of honeybees together with Laurent’s electronic music. The result momentarily unites an array of acoustic communities into a polyphonic interspecies composition.

Graphic design: Dimitri Jeannottat

Mastering: Bob Bellerue

Copy editing: Ellen Lapper

A special thanks to Souaf Hassan, Mohamed Ounih, Gilles Aubry, and the art space LE 18 in Marrakesh.

Hive (Albanian: Zgjoi) is based on the true story of a woman, Fahrije, who goes against misogynistic societal expectations to become an entrepreneur after her husband went missing during the 1998-1999 Kosovo War. She starts selling her own ajvar and honey, recruiting other women in the process. Fahrije’s husband has been missing since the war in Kosovo, and along with their grief, her family is struggling financially. In order to provide for them she launches a small agricultural business, but in the traditional patriarchal village where she lives, her ambition and efforts to empower herself and other women are not seen as positive things. She struggles not only to keep her family afloat but also against a hostile community who is rooting for her to fail.

(Wikipedia 2022)

Film still (01:19:03)

Film still (00:46:24)

Film still (00:32:42)

Film still (00:20:21)

Film still (00:21:11)

Film still (01:18:43)

Film still (01:18:51)

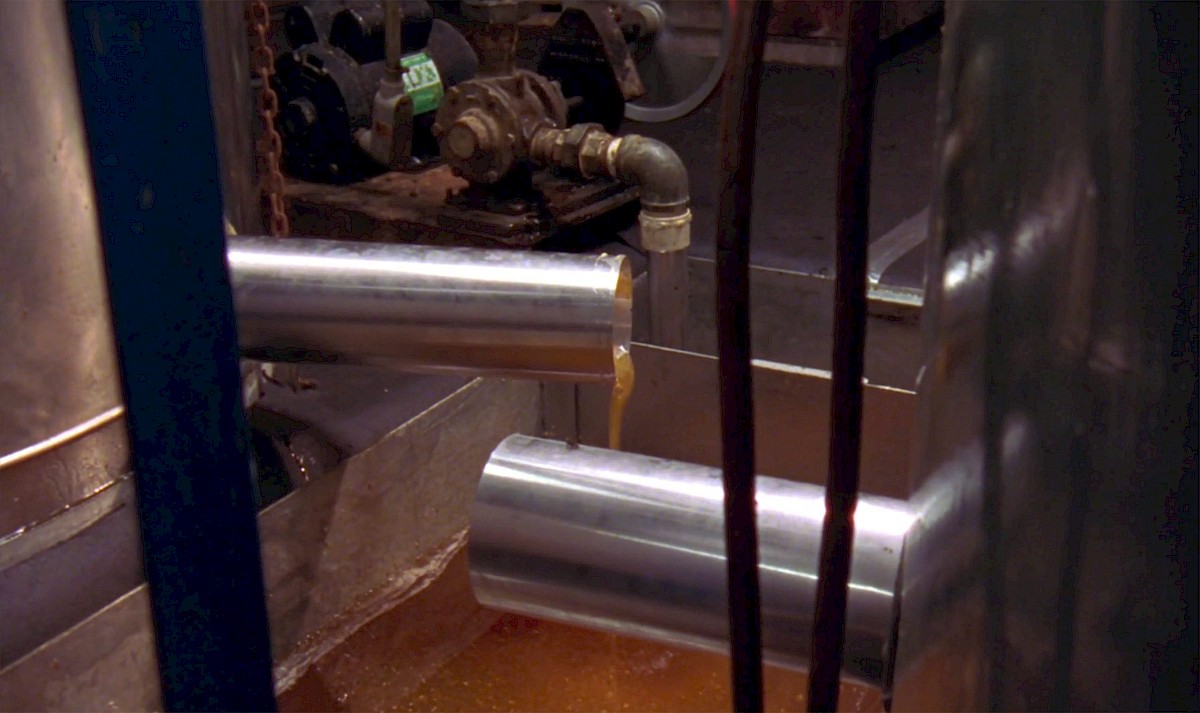

More than Honey is a Swiss documentary directed by Markus Imhoof about honeybee in California, Switzerland, China and Austria.

http://www.morethanhoneyfilm.com/

Film still (00:12:48)

Film still (00:03:16)

Film still (00:25:42)

Film still (00:25:13)

Film still featuring Prof. Dr. Randolf Menzel (00:15:30)

Film still (00:32:19)

Film still (00:12:03)

Film still (01:20:58)

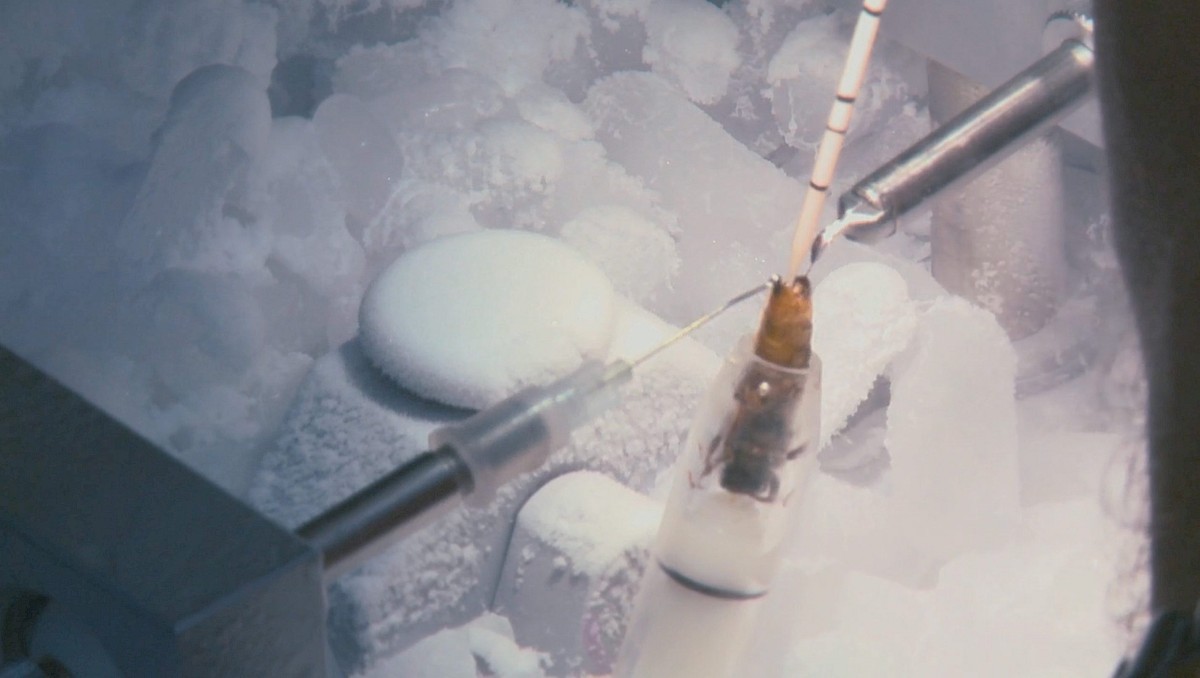

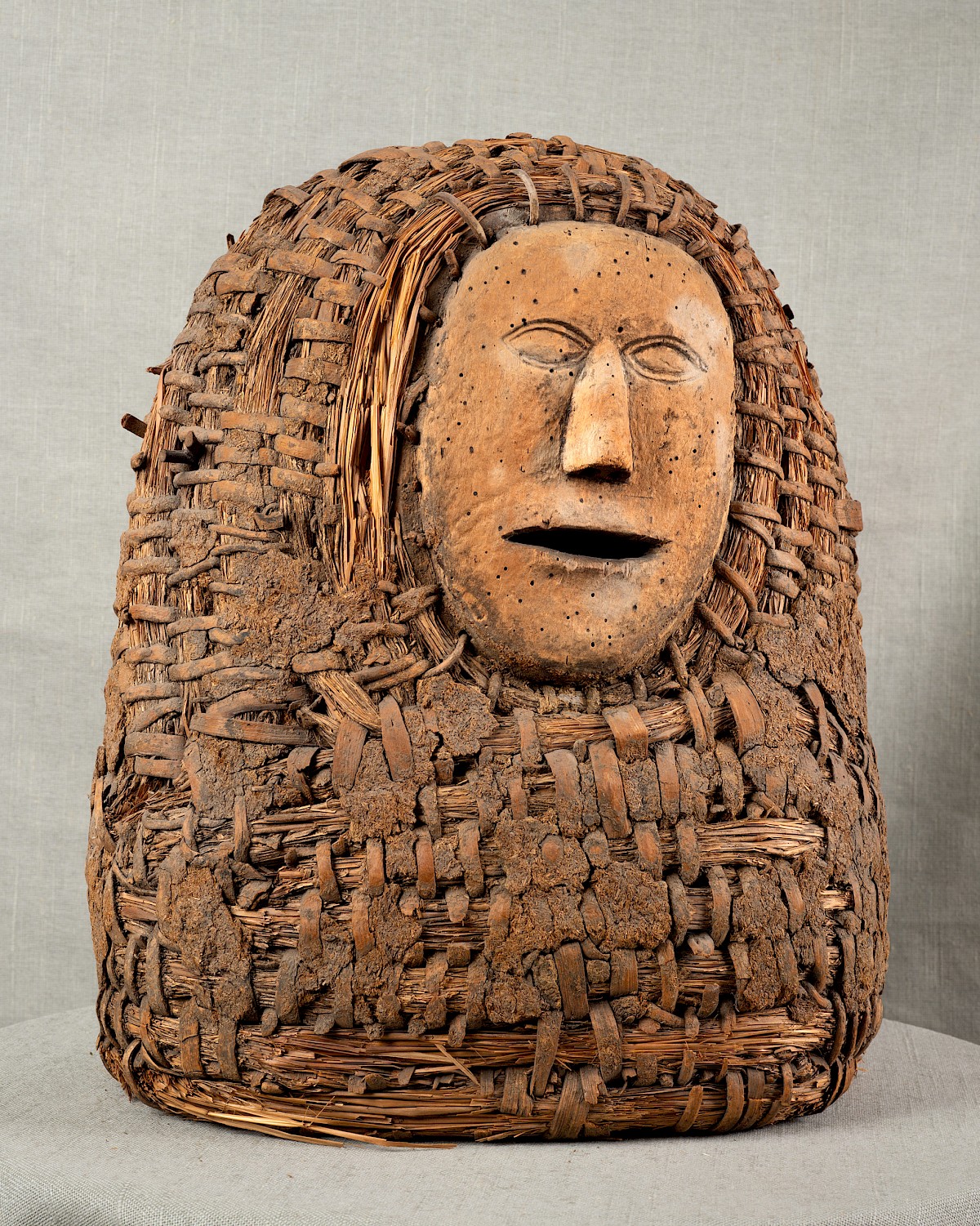

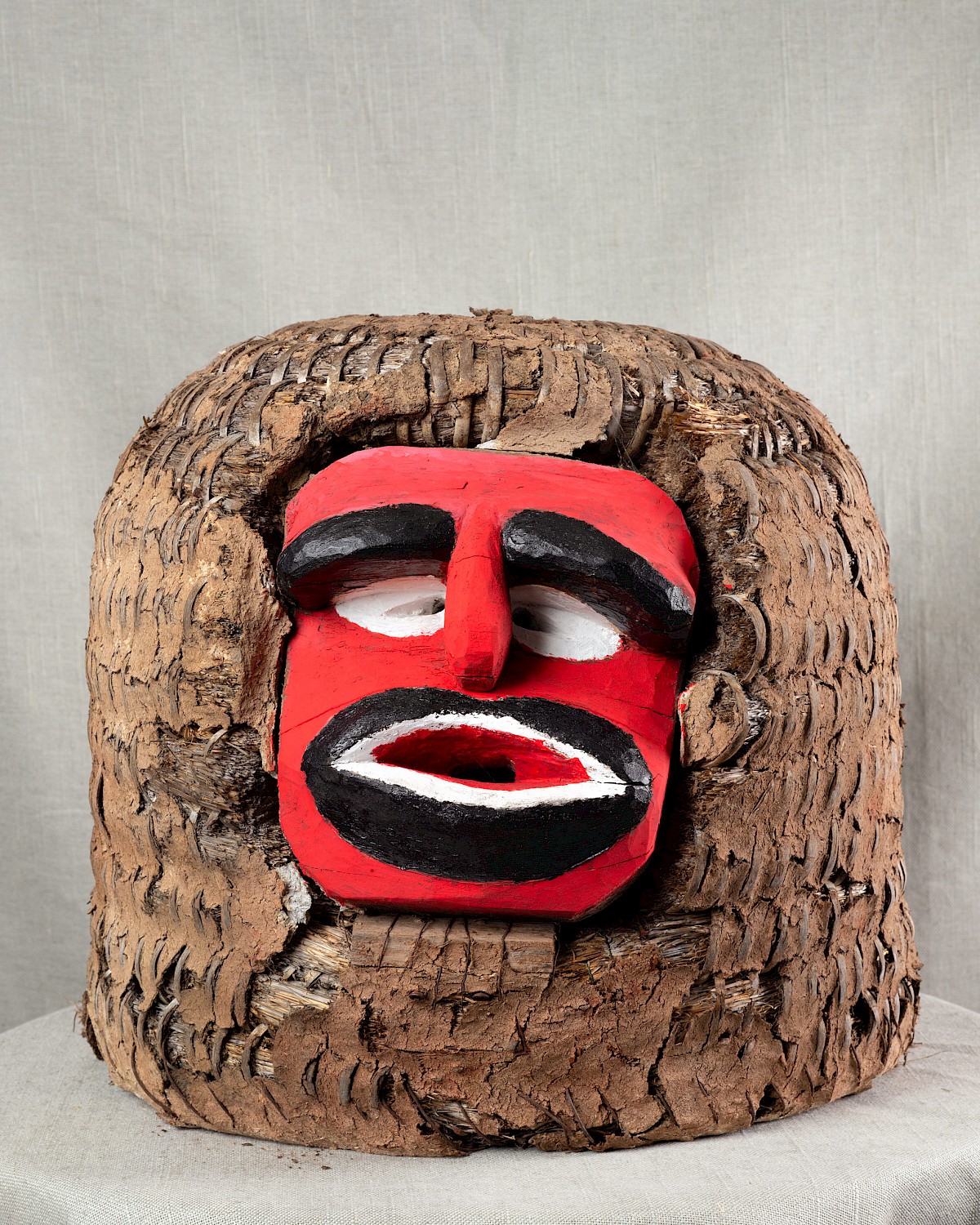

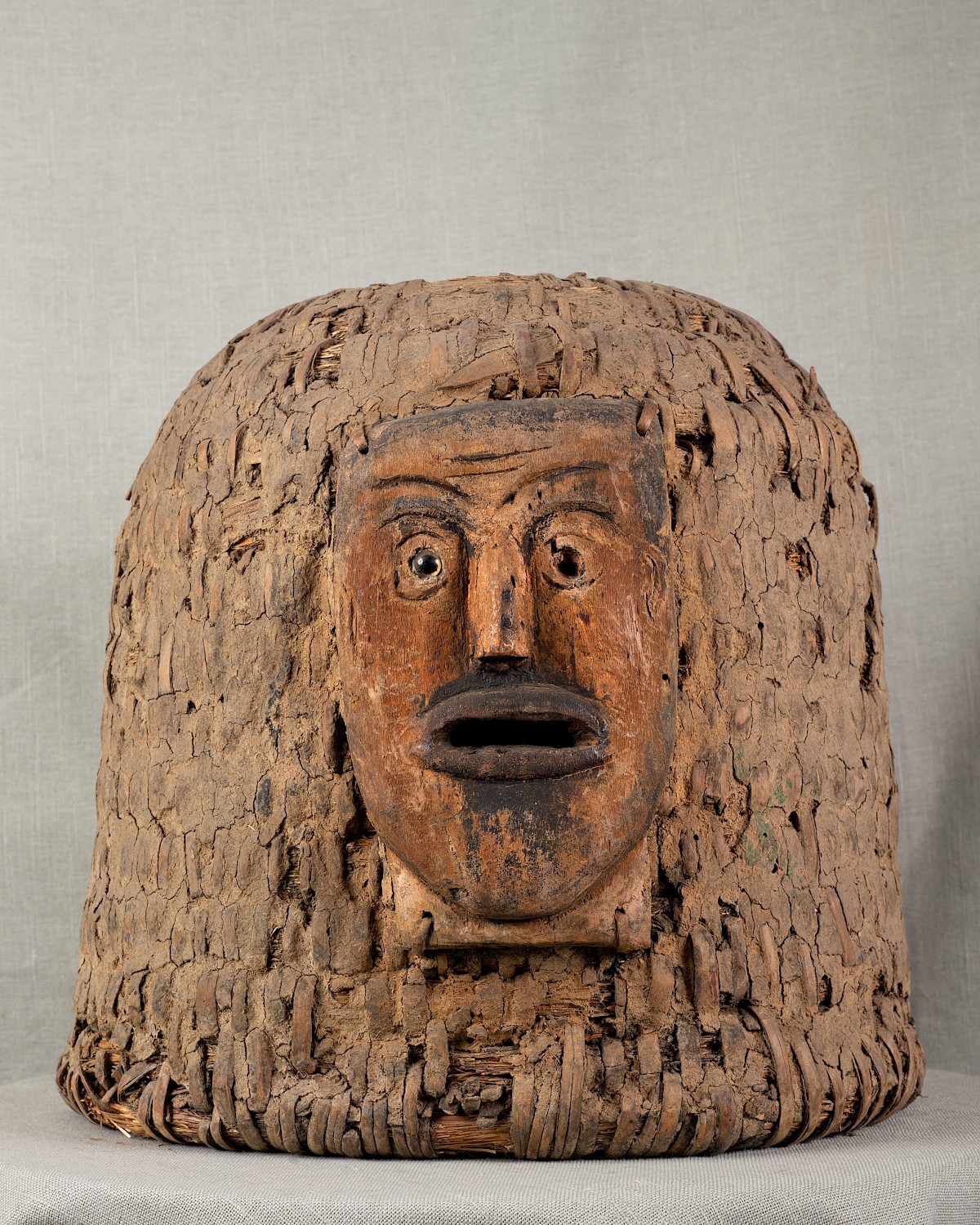

Bannkorb with a mask, flight holes: mouth, nostrils, and eyes, 52 × 46 cm, circa 1880, provenance: near Soltau, now: Heimatbund Museum Soltau.

Bannkorb with a mask, flight holes: mouth and nostrils, 39×38 cm, circa 1850, provenance: Rotenburg District, now: Historisches Museum Hannover.

Bannkorb with a mask, flight holes: mouth, nostrils, and eyes, 47×41 cm, 1880-99, previous ownership: unknown, now: Historisches Museum Hannover.

Bannkorb with a mask, flight hole: mouth, 51×37 cm, 1859, previous ownership: unknown, now: Historisches Museum Hannover.

Bannkorb with a mask, flight holes: mouth (main), nostrils, and eyes, 44×42 cm, 1875, provenance: M. Lüdemann, now: Historisches Museum Domherrenhaus Verden.

Bannkorb with a mask, flight holes: mouth (main), nostrils, and eyes, 44×42 cm, 1875, provenance: M. Lüdemann, now: Historisches Museum Domherrenhaus Verden.

Bannkorb with a mask, flight holes: mouth, nostrils, and eyes, 45 × 37 cm, date unknown, provenance: Kaiser, Westen, now: Historisches Museum Domherrenhaus Verden.

Bannkorb with a mask, flight holes: mouth (main) and nostrils, 52×45 cm, 1815, provenance: Brümmerhof near Soltau, now: Heimatverein Peetshof Wietzendorf e.V.

Bannkorb with a mask, flight holes: mouth (main) and nostrils, 43 × 40 cm, 1820-25, provenance: Lüneburg Heath, now: Heimatverein Peetshof Wietzendorf e.V.

The Scottish Beekeeper: Magazine of the Scottish Beekeepers’ Association, Vol. XLVII No. 7

The Scottish Beekeeper: Magazine of the Scottish Beekeepers’ Association, Vol. XLVII No. 7 (July 1970)

Softcover. Size: 18.7 (W) × 24.2 cm (H).

Bannkorb with a mask, flight holes: mouth (main) and nostrils, 51×34 cm, date unknown, previous ownership: unknown, now: Deutsches Bienenmuseum Weimar.

Bannkorb with a mask, flight holes: mouth (main) and nostrils, 44 × 38 cm, date unknown, previous ownership: unknown, now: Heidemuseum Rischmannshof Walsrode.

Bannkorb with a mask, flight hole: mouth, 41×37 cm, circa 1970, previous ownership: unknown, now: Heidemuseum Rischmannshof Walsrode.

The Scottish Beekeeper: Magazine of the Scottish Beekeepers’ Association, Vol. XLIX No. 8

The Scottish Beekeeper: Magazine of the Scottish Beekeepers’ Association, Vol. XLIX No. 8 (August 1972)

Softcover, pp. 140-151. Size: 18.7 (W) × 24.2 cm (H).

Principal contents:

Bannkorb with a mask, flight hole: mouth, 41×37 cm, circa 1970, previous ownership: unknown, now: Heidemuseum Rischmannshof Walsrode.

The Scottish Beekeeper: Magazine of the Scottish Beekeepers’ Association, Vol. XLIX No. 5

The Scottish Beekeeper: Magazine of the Scottish Beekeepers’ Association, Vol. XLIX No. 5 (May 1972)

Softcover, pp. 92-103. Size: 18.7 (W) × 24.2 cm (H).

Principal contents:

Bannkorb with a mask, flight holes: mouth, 45 × 42 cm, 1741, previous ownership: unknown, now: Heidemuseum Rischmannshof Walsrode.

The Scottish Beekeeper: Magazine of the Scottish Beekeepers’ Association, Vol. XLIII No. 5

The Scottish Beekeeper: Magazine of the Scottish Beekeepers’ Association, Vol. XLIII No. 5 (May 1966)

Softcover, pp. 88-98. Size: 18.7 (W) × 24.2 cm (H).

Principal contents:

Bannkorb with a mask, flight holes: mouth, nostrils, and eyes, 40×36 cm, second half of the 18th century/first half of the 19th century, previous ownership: unknown, now: Museum Nienburg.

The Scottish Beekeeper: Magazine of the Scottish Beekeepers’ Association, Vol. XLVII No. 8 (August 1970)

Softcover, pp. 140-151. Size: 18.7 (W) × 24.2 cm (H).

Principal contents:

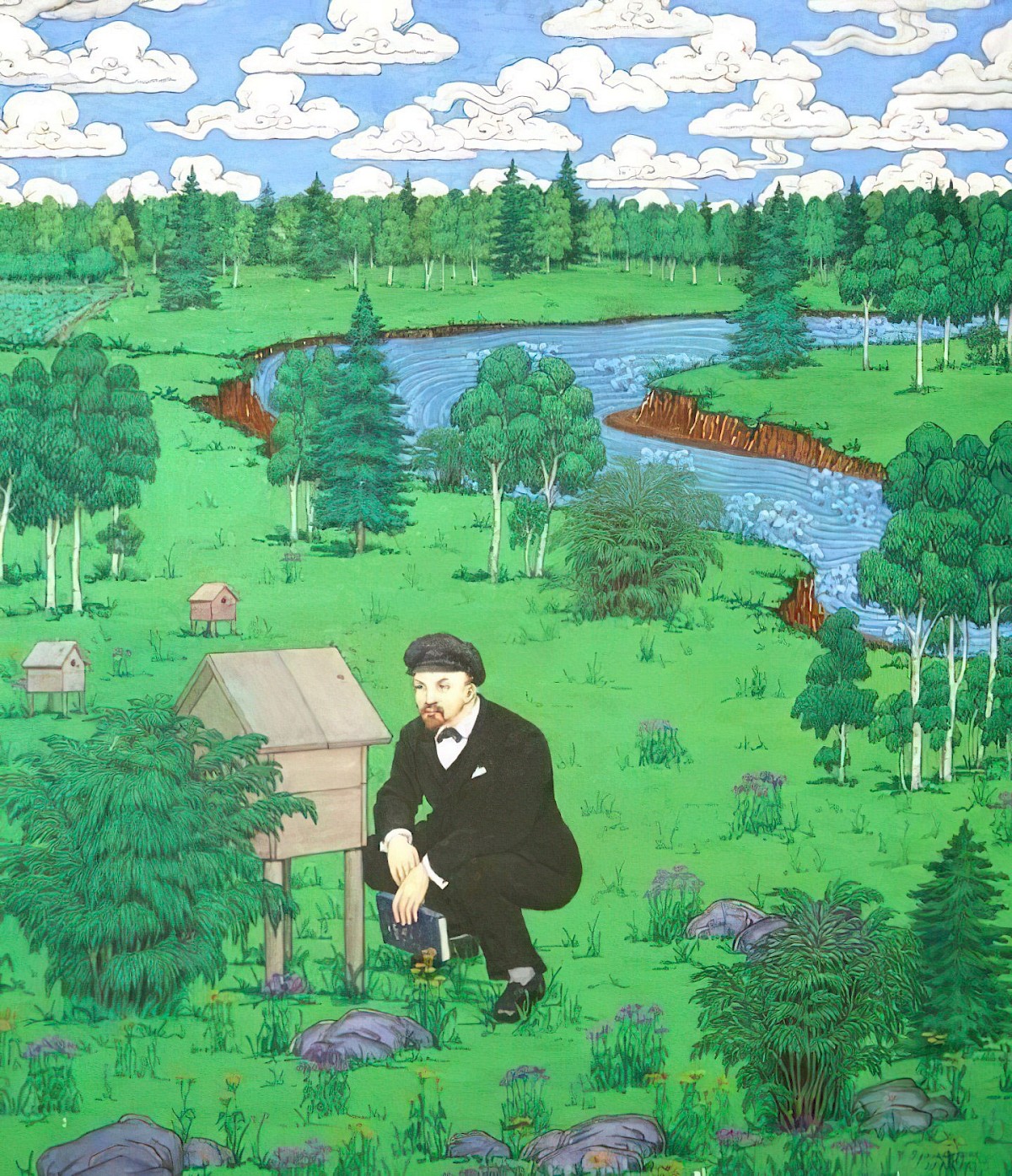

Lenin as a Beekeeper, painting by Ürjingiin Yadamsüren, Mongolian People’s Republic, 1970

Bannkorb with a front panel, flight holes: mouths, 68×34 cm, second half of the 18th century/ first half of the 19th century, previous ownership: unknown, now: Museum Nienburg.

“Spring Day, Apiary” by Serhiy (Sergey Ivanovich) Svetoslavsky, 1899. Oil on canvas, size: 174 (W) × 138 cm (H). Odessa Fine Art Museum, Ukraine.

Bannkorb with a mask, flight holes: mouth and eyes, 44×39.5 cm, second half of the 18th century/first half of the 19th century, previ- ous ownership: unknown, now: Museum Nienburg.

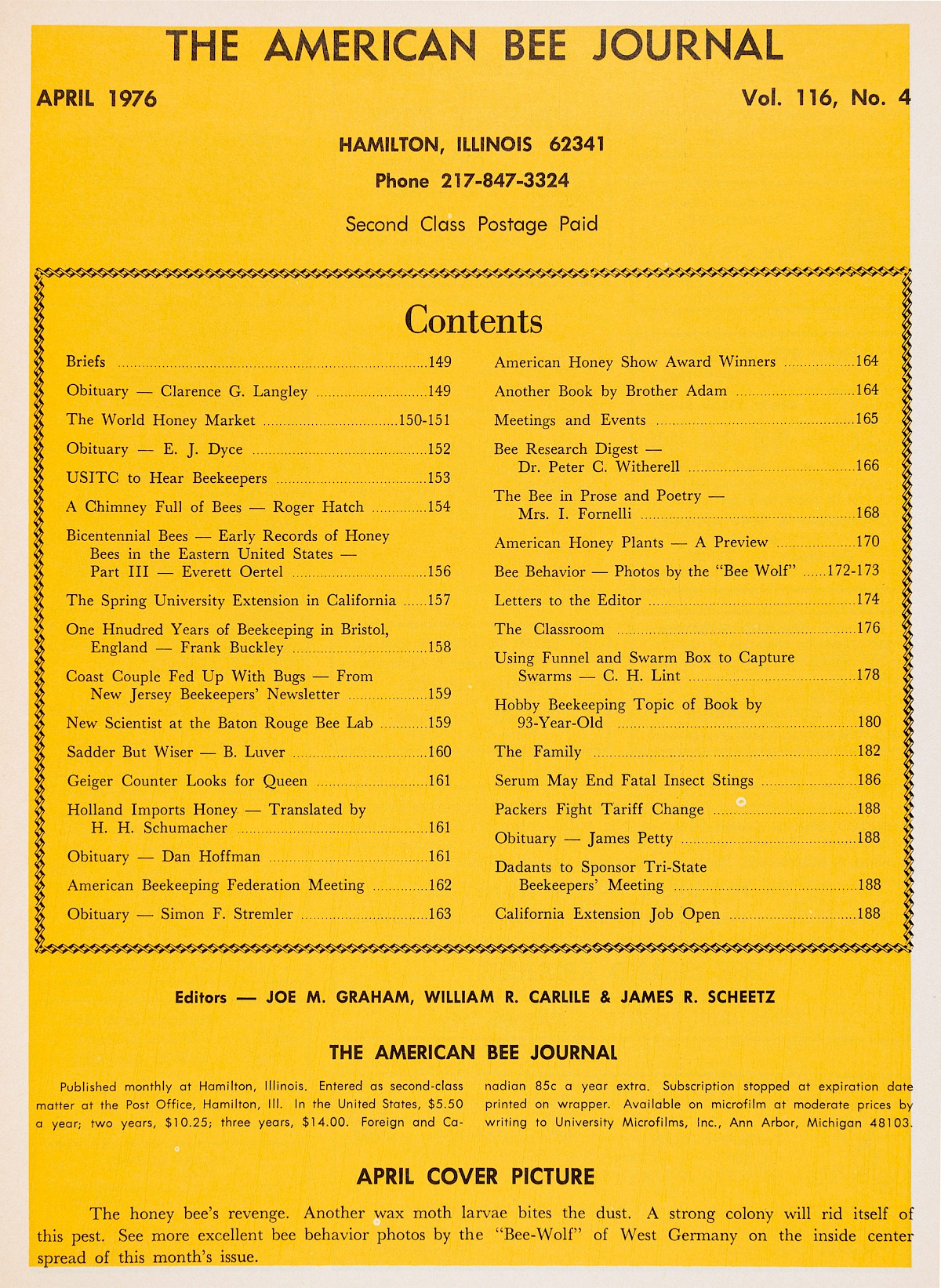

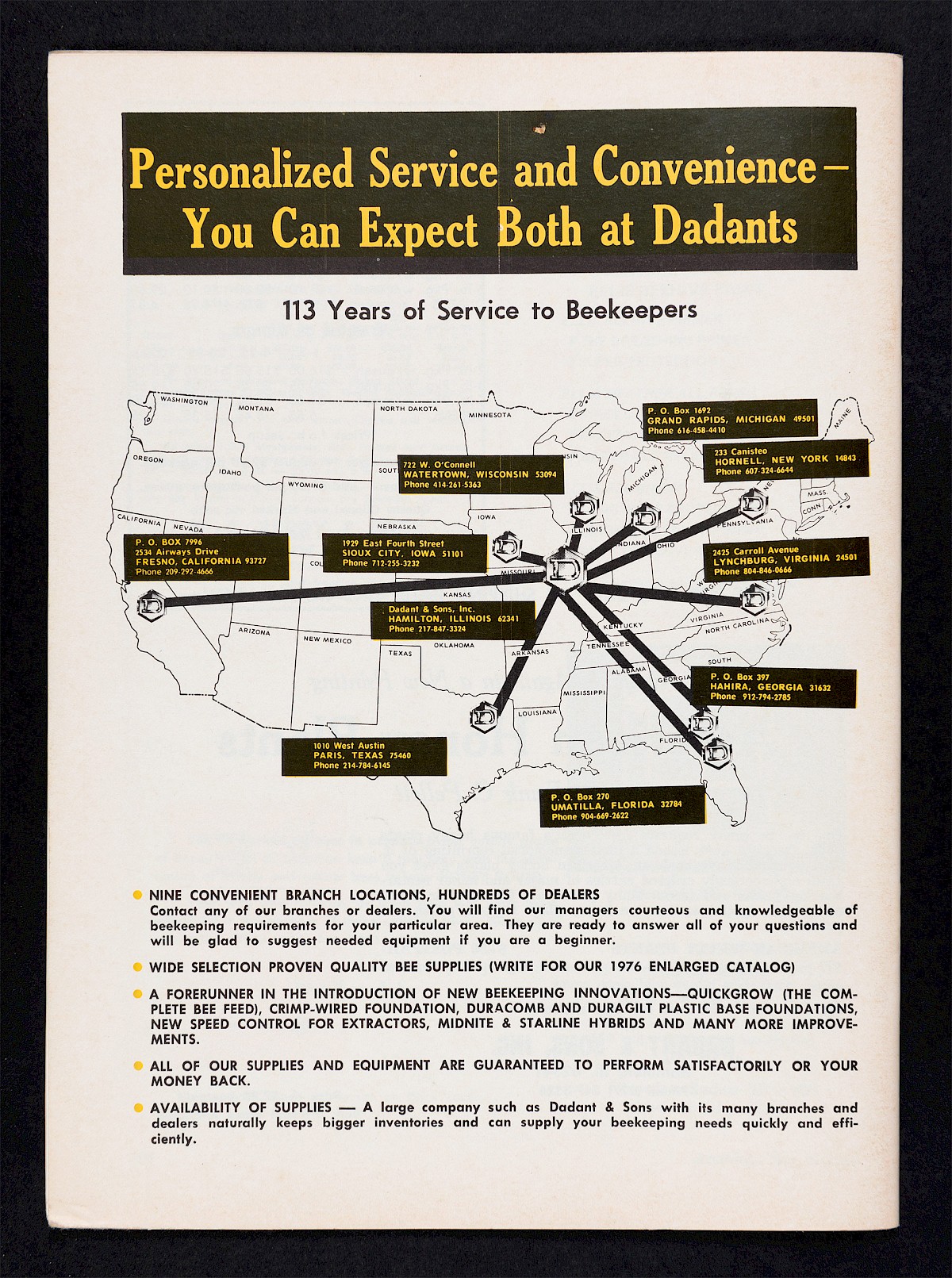

American Bee Journal, Vol. 116 No.4 (April 1976)

Softcover. Size: 20.3 (W) × 27.9 cm (H).

Bannkorb with a mask and hat, flight holes: mouth and nostrils, 60×42 cm, second half of the 19th century, previous ownership: unknown, now: Museum Nienburg.

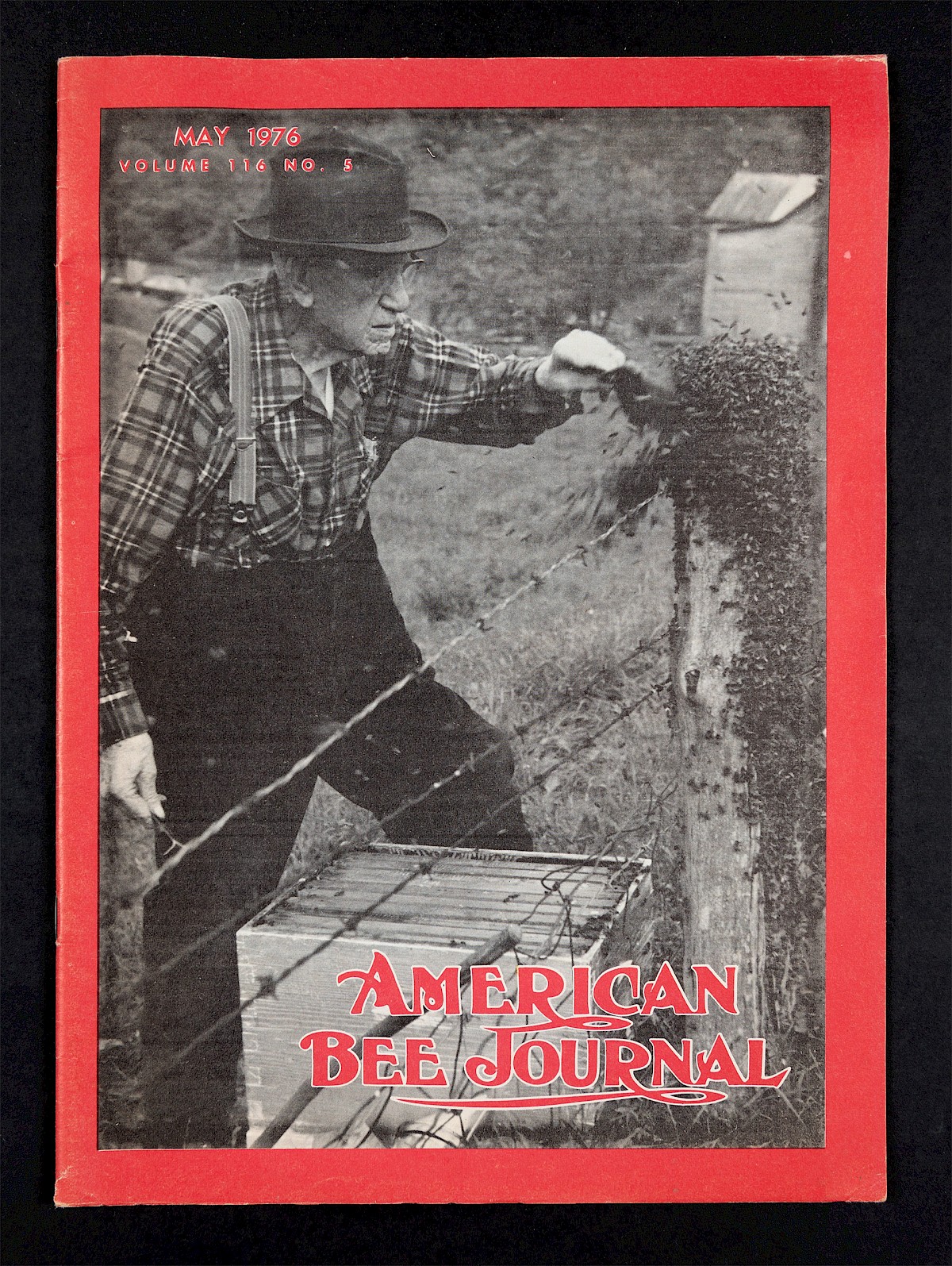

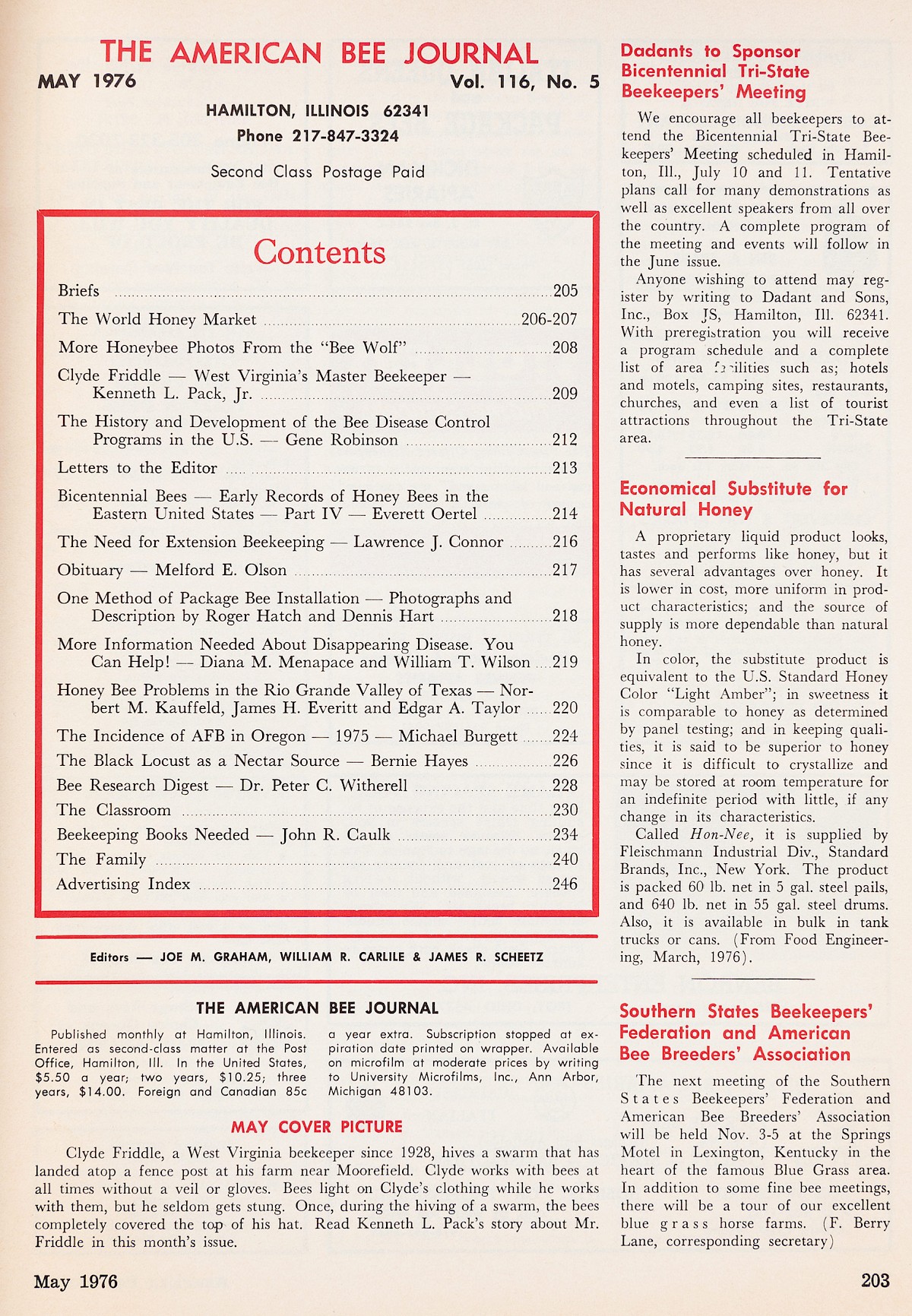

American Bee Journal, Vol. 116 No.5 (May 1976)

Softcover. Size: 20.3 (W) × 27.9 cm (H).

Bannkorb with a mask, flight holes: mouth and nostrils, 46×40 cm, second half of the 18th century, previous ownership: unknown, now: Museum Nienburg.

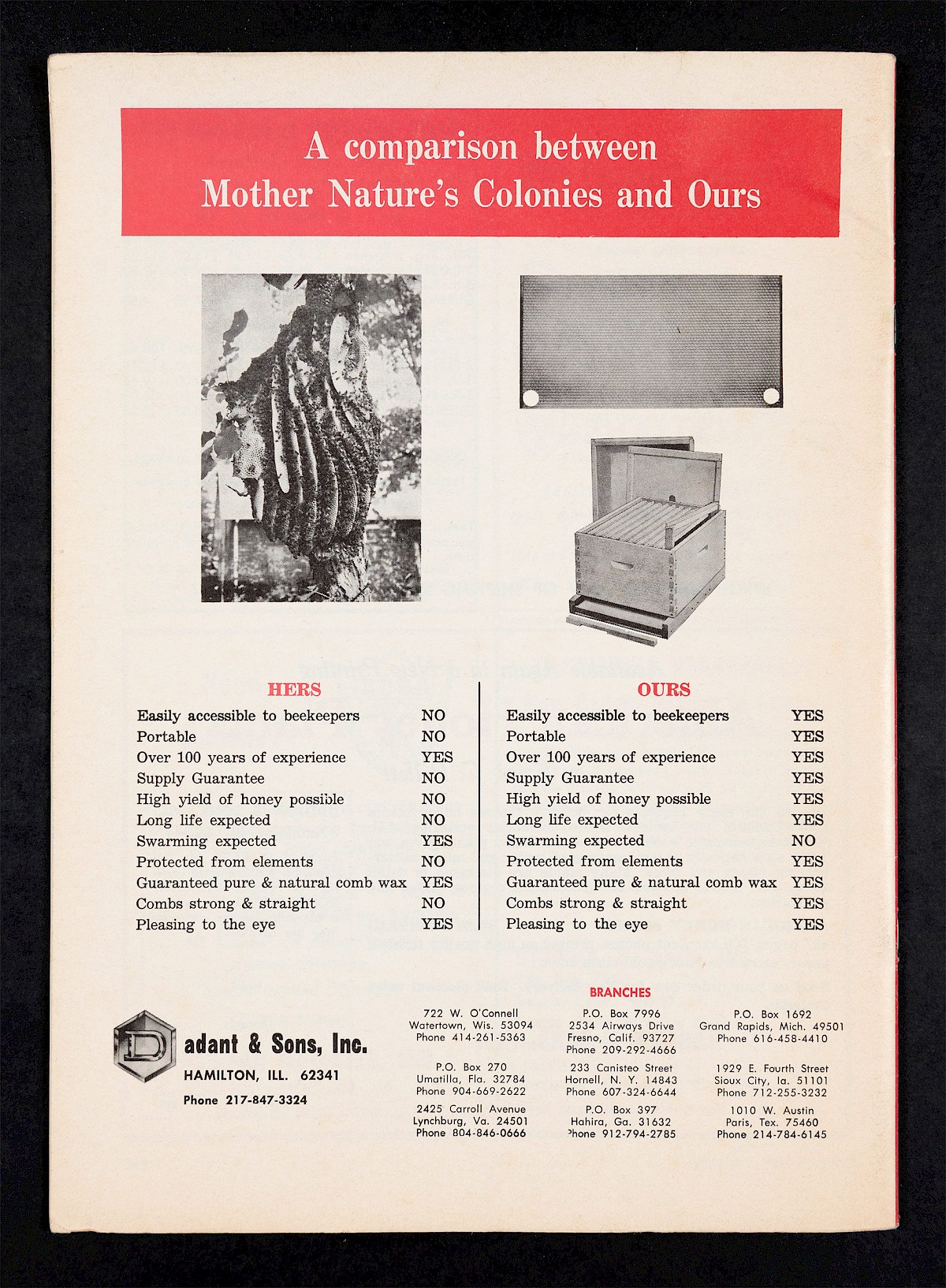

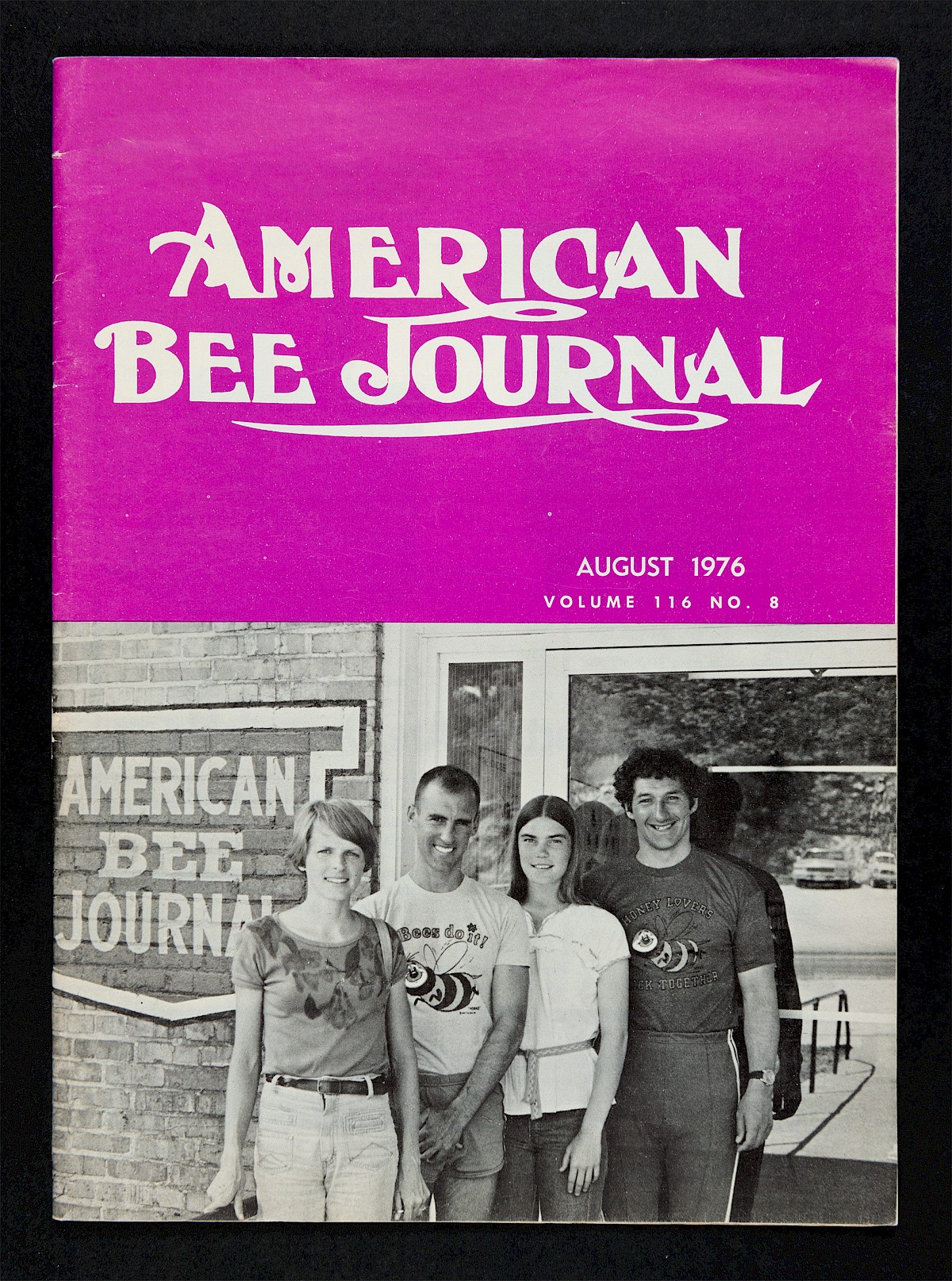

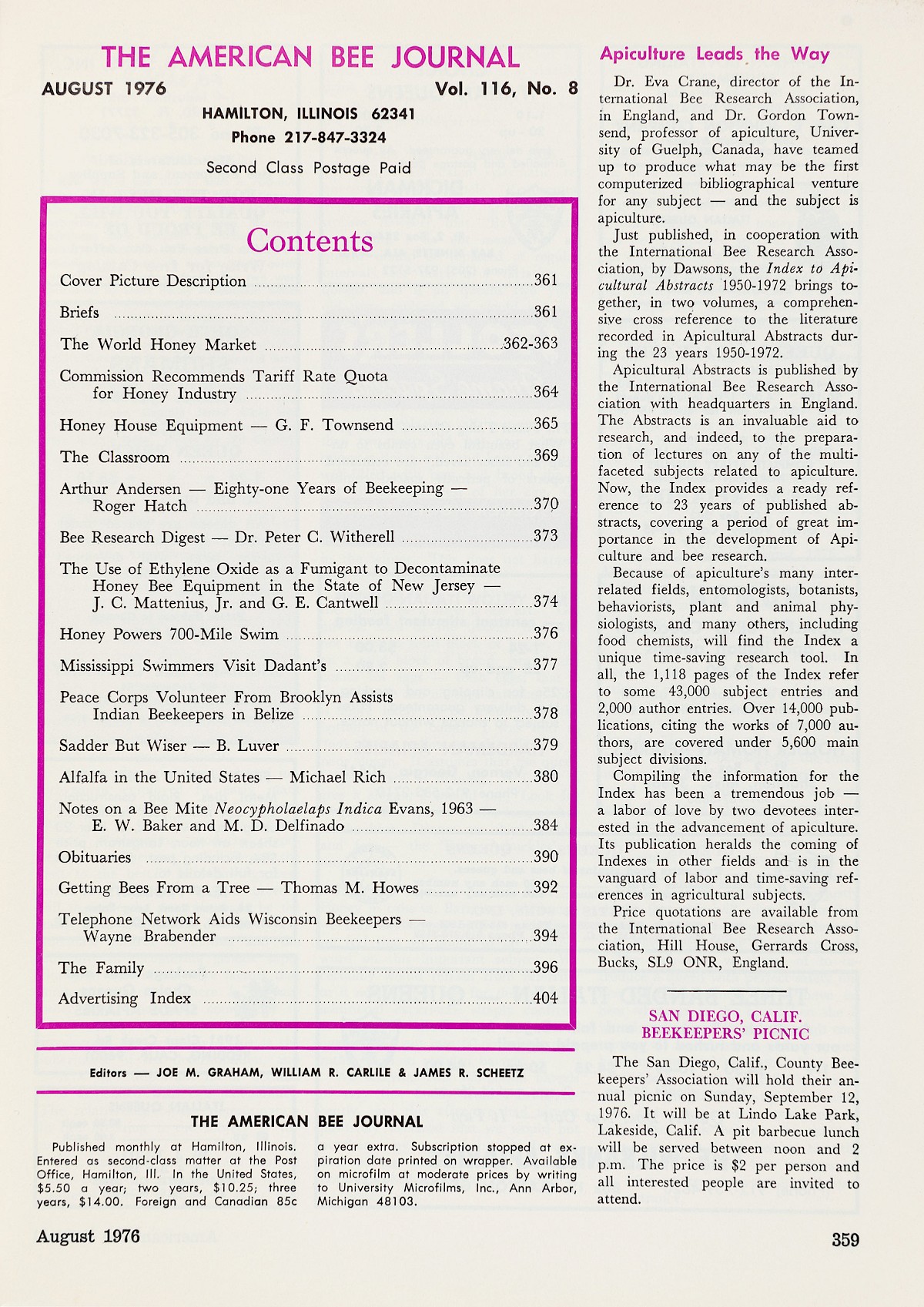

American Bee Journal, Vol. 116 No.8 (August 1976)

Softcover. Size: 20.3 (W) × 27.9 cm (H).

Bannkorb with a front panel, flight hole: mouth, 50×35 cm, 1808, previous ownership: unknown, now: Museum Nienburg.

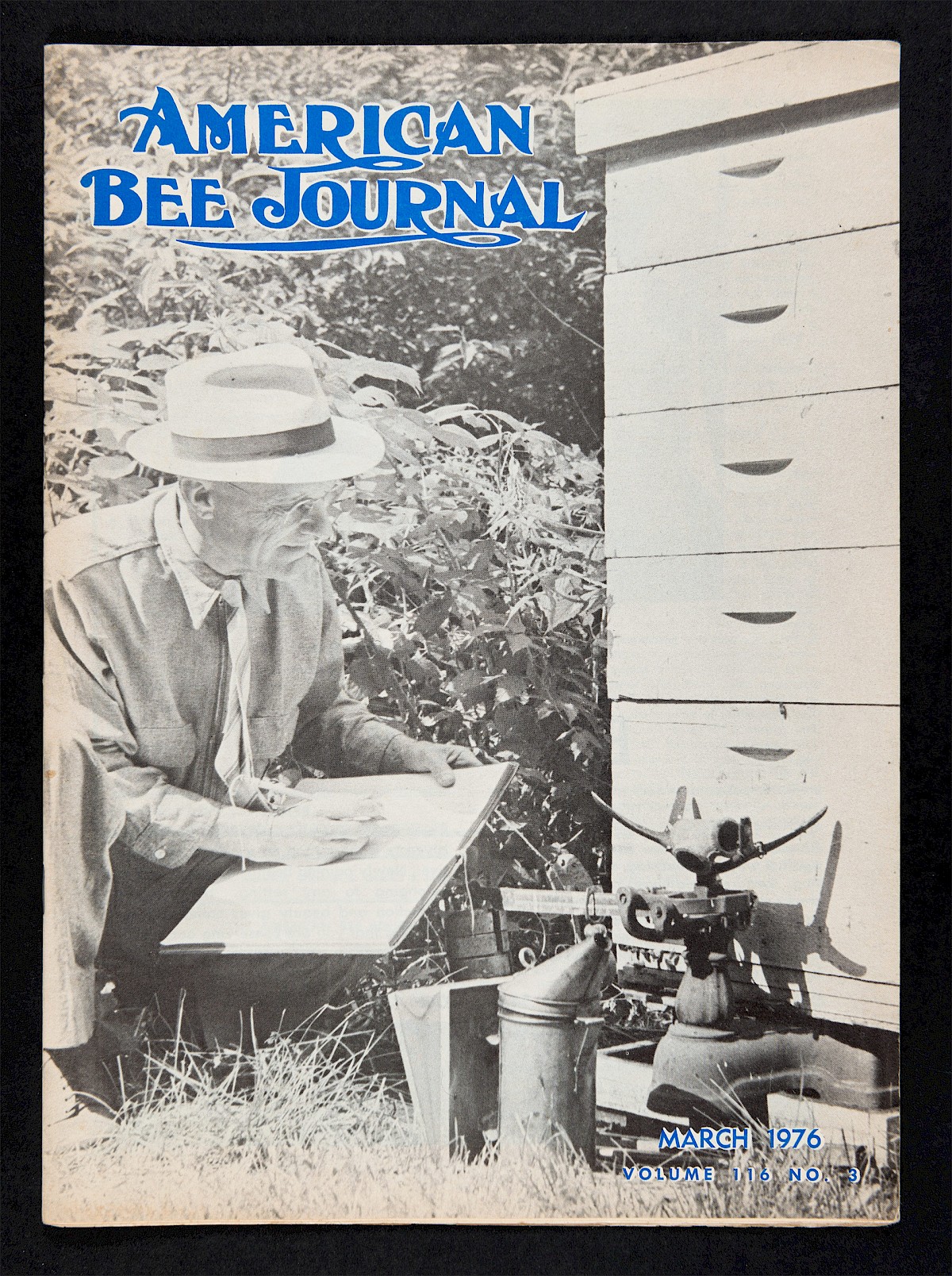

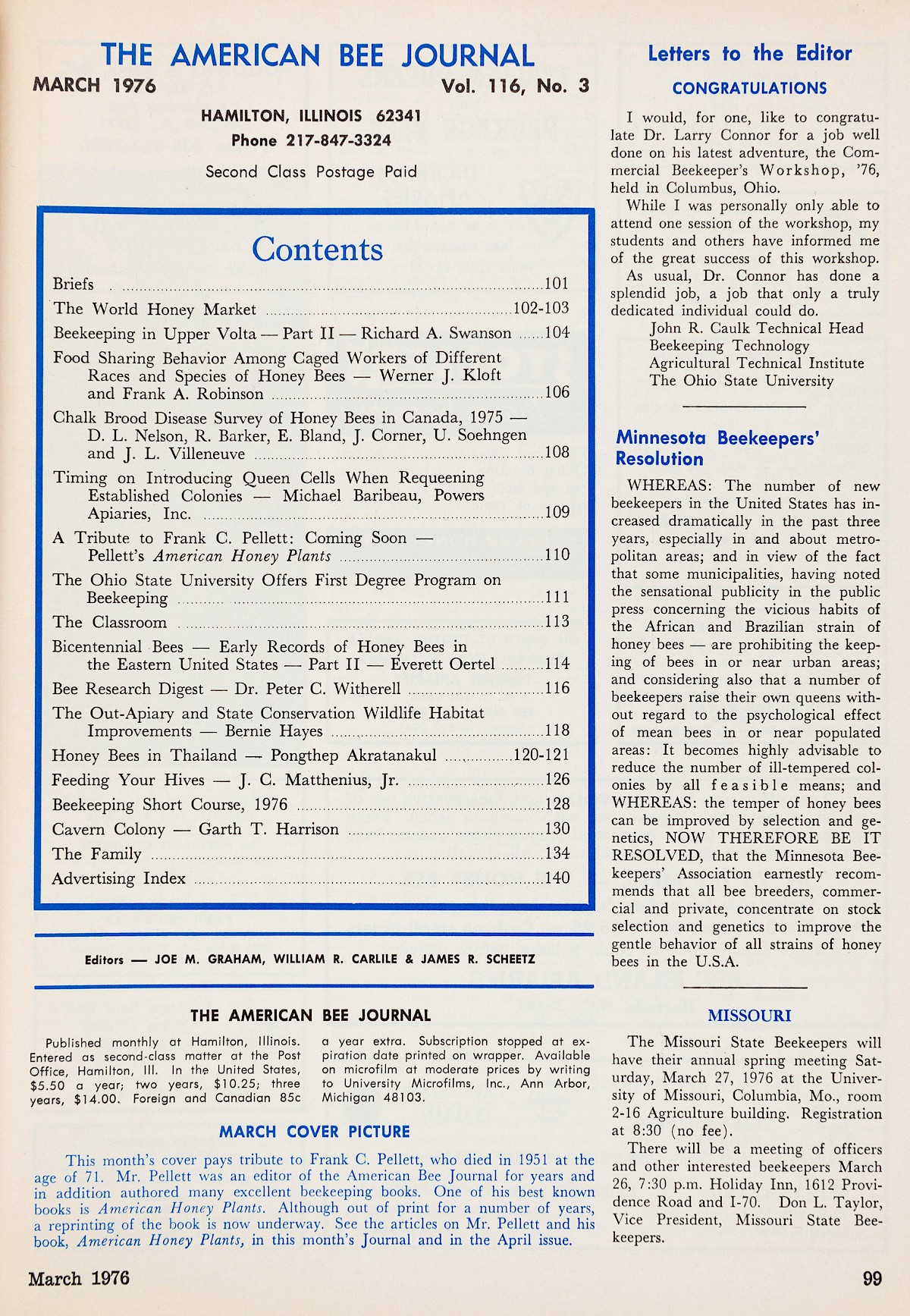

American Bee Journal, Vol. 116 No.3 (March 1976)

Softcover. Size: 20.3 (W) × 27.9 cm (H).

Bannkorb with a mask, flight holes: mouth and eyes, 43 × 41 cm, unknown, previous ownership: date unknown, now: Wilhelm Haase-Bruns’s private collection.

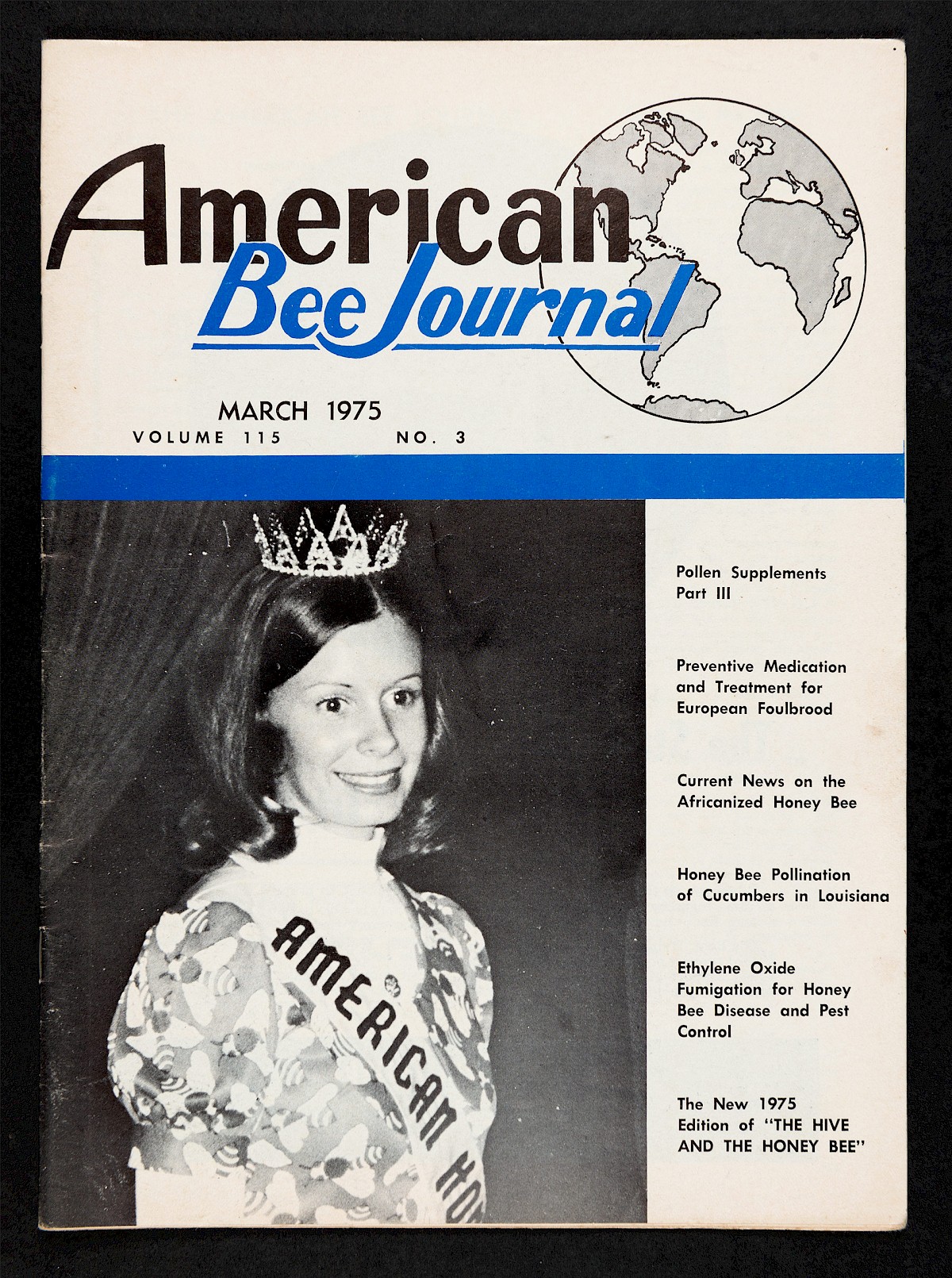

American Bee Journal, Vol. 115 No.3 (March 1975)

Softcover. Size: 20.3 (W) × 27.9 cm (H).

Bannkorb with a mask, flight holes: mouth and eyes, 43 × 41 cm, unknown, previous ownership: date unknown, now: Dieter Röpke’s private collection.

Bannkorb with a mask, flight holes: mouth and eyes, 44×41 cm, date unknown, previous ownership: unknown, now: Zeidel-Museum Feucht.

American Bee Journal, Vol. 116 No.2 (February 1976)

Softcover. Size: 20.3 (W) × 27.9 cm (H).

Bannkorb with a mask, flight holes: mouth and eyes, 47×40 cm, date unknown, previous ownership: unknown, now: Zeidel-Museum Feucht.

American Bee Journal, Vol. 115 No.11 (November 1975)

Softcover. Size: 20.3 (W) × 27.9 cm (H).

Bannkorb with a mask, flight hole: mouth, 43×41 cm, date unknown, previous ownership: un- known, now: Zeidel-Museum Feucht.

American Bee Journal, Vol. 116 No.7 (July 1976)

Softcover. Size: 20.3 (W) × 27.9 cm (H).

Bannkorb with shoulders and a mask, flight hole: mouth, 47×42 cm, before 1930, previous ownership: unknown, aktuell: Institut für Bienenkunde Celle.

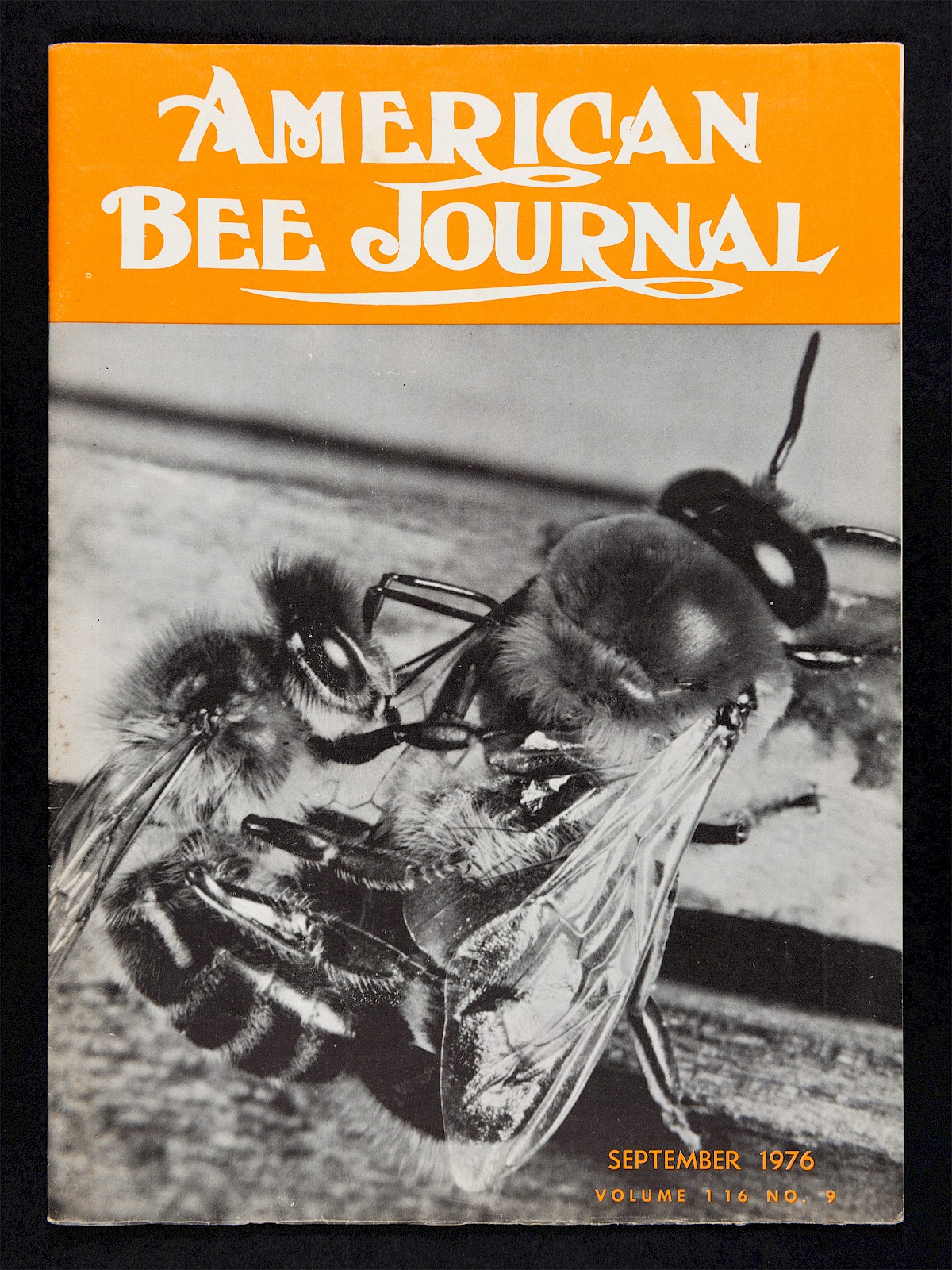

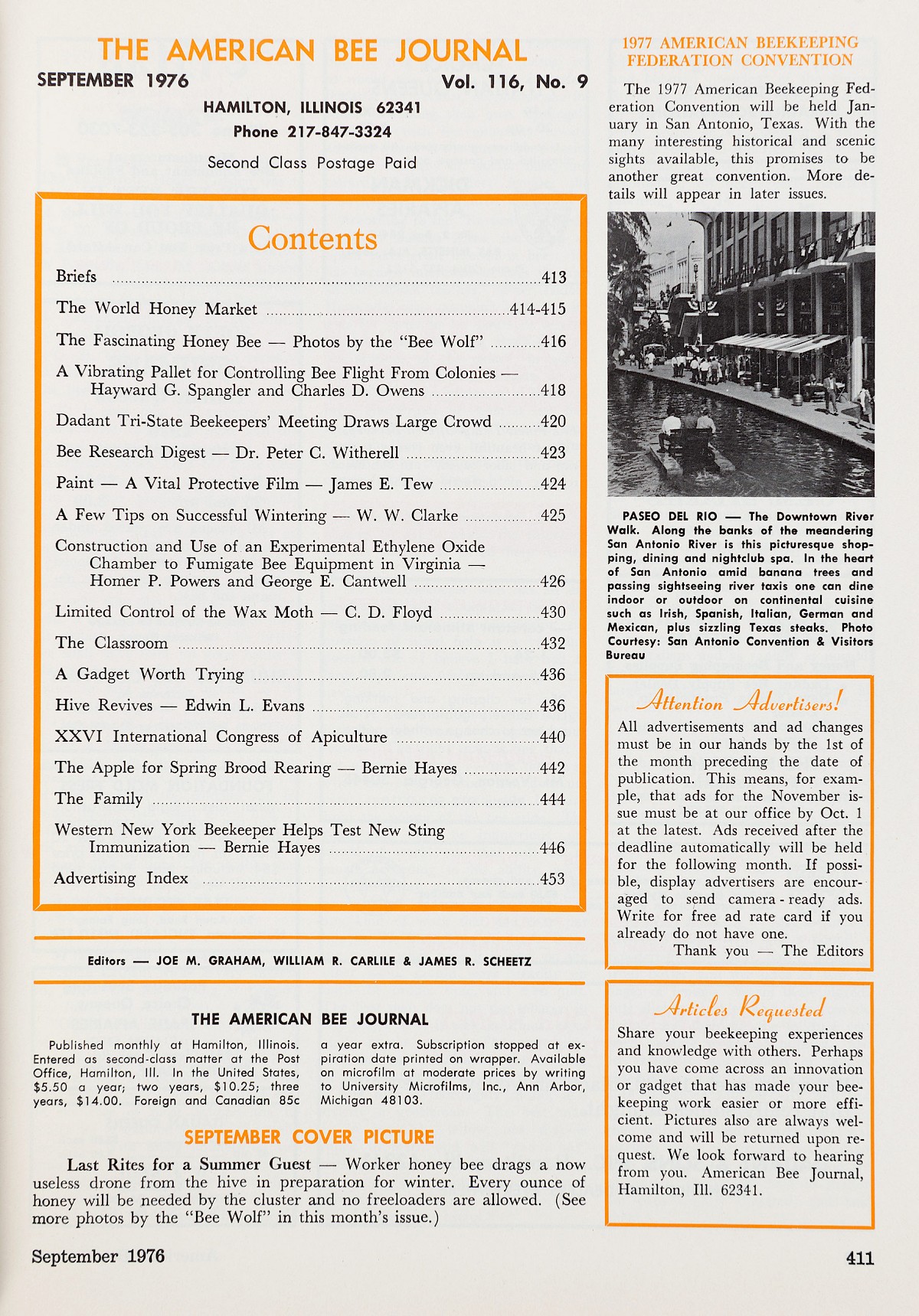

American Bee Journal, Vol. 116 No.9 (September 1976)

Softcover. Size: 20.3 (W) × 27.9 cm (H).

Bannkorb with a mask, flight holes: mouth, 43×45 cm, date unknown, previous ownership: unknown, now: Institut für Bienenkunde Celle.

American Bee Journal, Vol. 116 No.10 (October 1976)

Softcover. Size: 20.3 (W) × 27.9 cm (H).

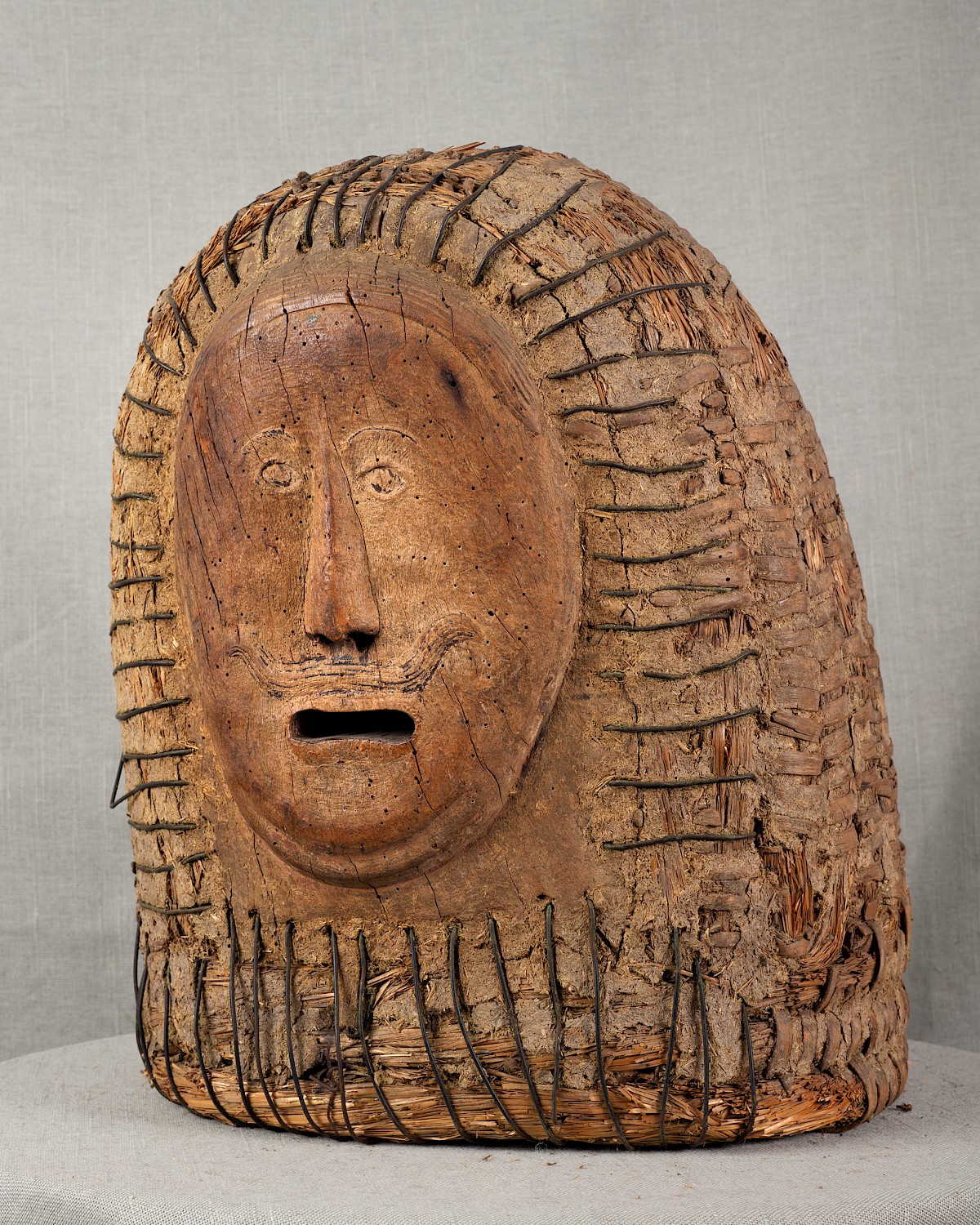

Bannkorb with a mask, flight holes: mouth and nostrils, 47 × 39 cm, date unknown, previous ownership: unknown, now: Institut für Bienenkunde Celle.

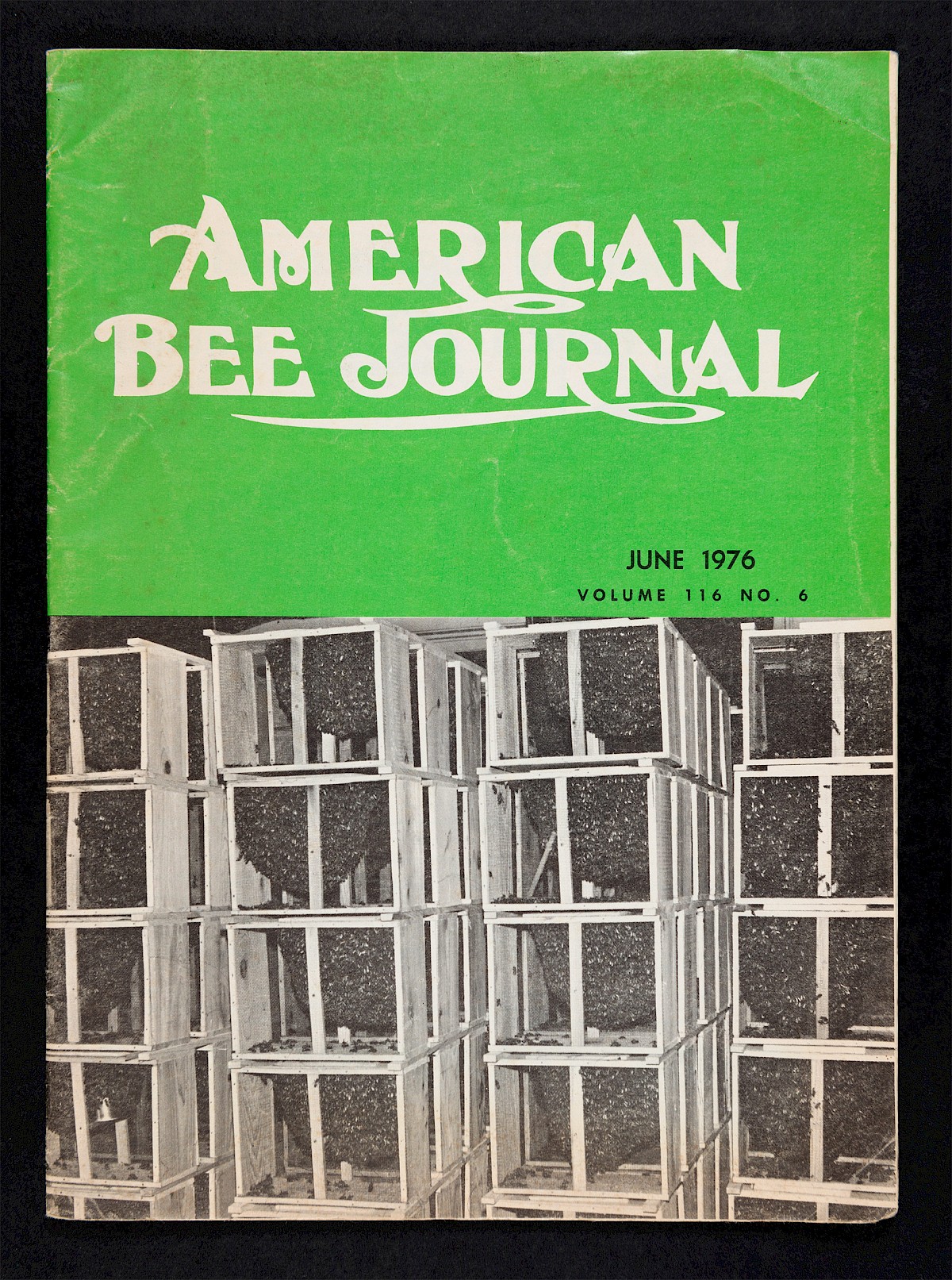

American Bee Journal, Vol. 116 No.6 (June 1976)

Softcover. Size: 20.3 (W) × 27.9 cm (H).

Bannkorb with a mask, flight holes: mouth and eyes, 48 × 37 cm, date unknown, previous ownership: unknown, now: Institut für Bienenkunde Celle.

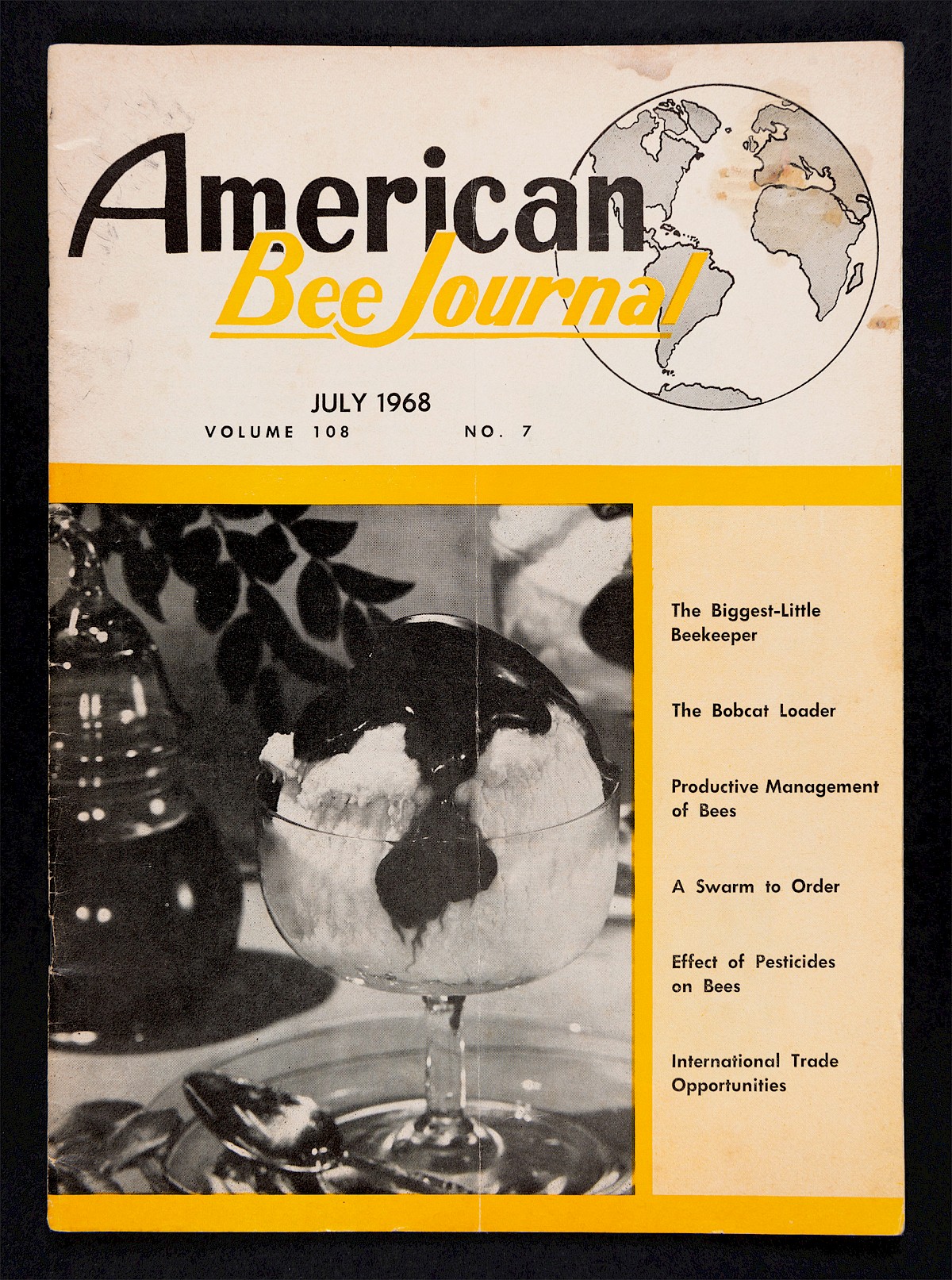

American Bee Journal, Vol. 108 No.7 (July 1968)

Softcover. Size: 20.3 (W) × 27.9 cm (H).

American Bee Journal, Vol. 109 No.9 (September 1969)

Softcover. Size: 20.3 (W) × 27.9 cm (H).

Bannkorb with a mask, flight hole: mouth, 50×40 cm, 1881, provenance: Lehrte, now: Institut für Bienenkunde Celle.

American Bee Journal, Vol. 114 No.2 (February 1974)

Softcover. Size: 20.3 (W) × 27.9 cm (H).

Bannkorb with a mask, flight hole: mouth, 46×41 cm, date unknown, previous ownership: unknown, now: Institut für Bienenkunde Celle.

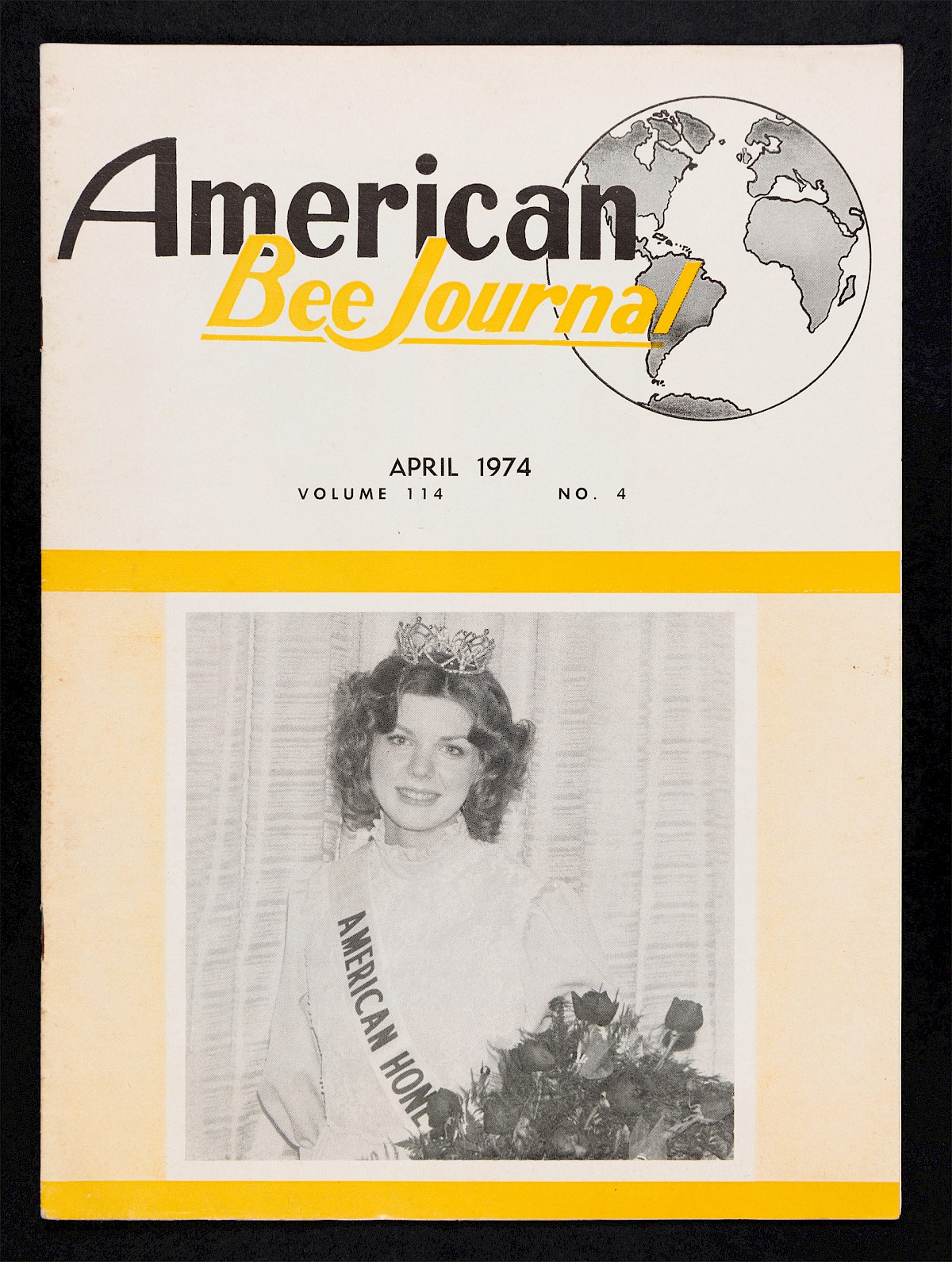

American Bee Journal, Vol. 114 No.4 (April 1974)

Softcover. Size: 20.3 (W) × 27.9 cm (H).

Bannkorb with a mask, flight hole: mouth, 45×43 cm, 1760, provenance: Dachtmissen near Burgdorf, now: Institut für Bienenkunde Celle.

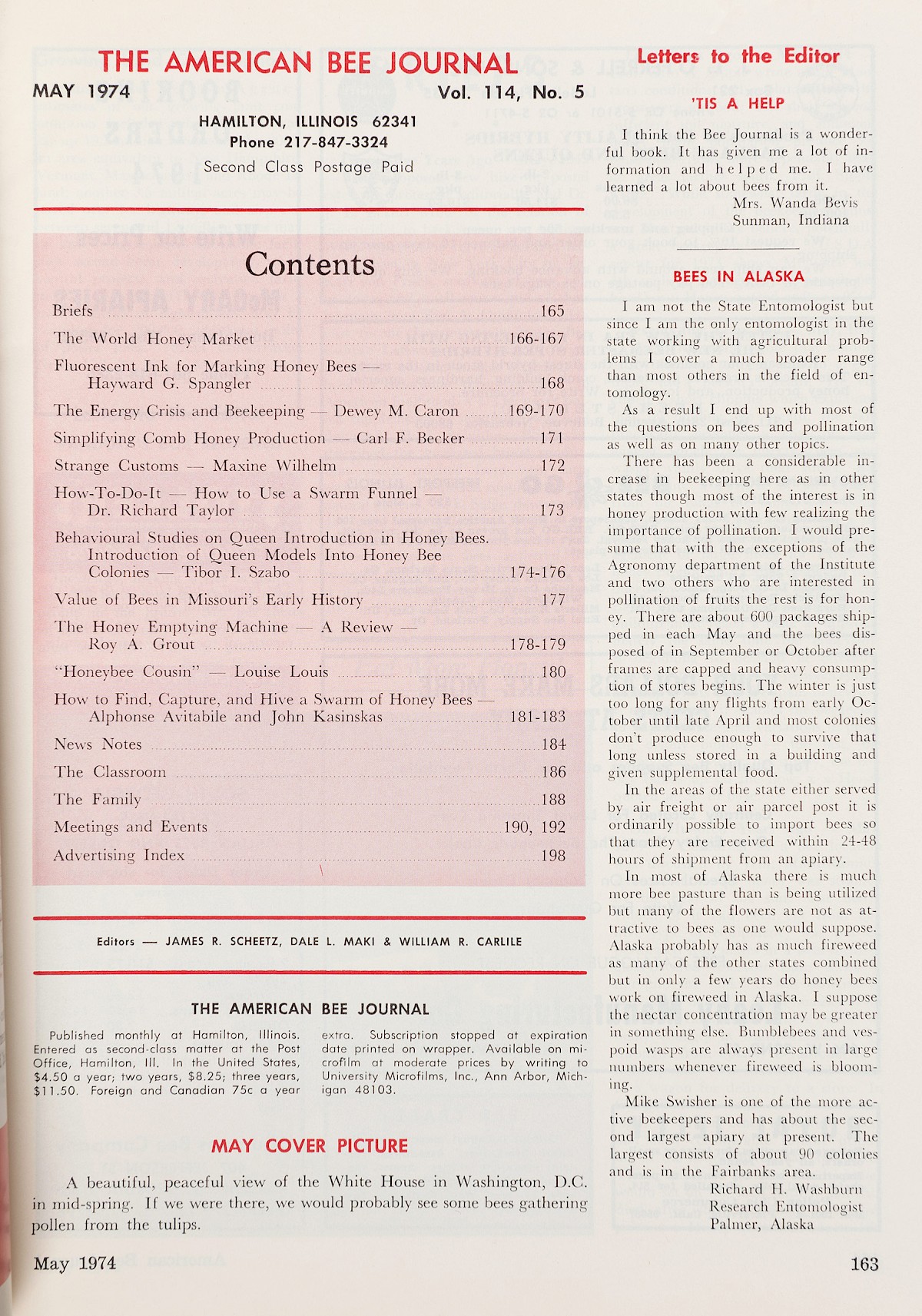

American Bee Journal, Vol. 114 No.5 (May 1974)

Softcover. Size: 20.3 (W) × 27.9 cm (H).

Bannkorb with a mask, flight hole: mouth, 44×41 cm, circa 1930, provenance: environs of Hermannsburg, Amme family in Uetze, now: Institut für Bienenkunde Celle.

Film still (00:00:48)

Ulee’s Gold is an American drama film directed by Victor Nuñez and starring Peter Fonda as the main actor. In short, Ulysses Jackson (nicknamed Ulee) is a Vietnam War veteran and a beekeeper that gets into trouble because of his son’s past. Jimmy (his son) his in prison for a bank heist and his former partners track down his wife and Ulee himself to try finding Jimmy’s share of the money left from the heist.

Film still (00:01:56)

Film still (00:02:41)

Film still (00:47:38)

Film still (00:48:04)

Film still (01:18:11)

Film still (01:49:38)

Bannkorb with a mask, flight hole: mouth, 37 × 32 cm, before 1932, provenance: Elliehausen near Göttingen, now: Institut für Bienenkunde Celle.

Bannkorb with a mask, flight holes: mouth, 35 × 31 cm, before 1932, provenance: Elliehausen near Göttigen, now: Institut für Bienenkunde Celle.

Bannkorb with shoulders and a mask, flight holes: mouth and nostrils, district of Celle, 67×64 cm, second half of the 18th century, provenance: Timme’s farm in Hassel, now: Institut für Bienenkunde Celle.

Bannkorb with a mask, flight holes: mouth, nostrils, and eyes, 45.5×41 cm, first half of the 20th century, provenance: Johannes Dehning’s apiary, Heidberg, in Hans-Günther Brockmann’s private collection since 1966.

Bannkorb with a mask, flight holes: mouth, nostrils, and eyes, 51.5×41 cm, circa 1850, previous ownership: unknown, now: Museum Römstedthaus.

Bannkorb with a mask, flight holes: mouth and under the chin, 42×28 cm, circa 1850, previous ownership: unknown, now: Museum Römstedthaus.

Bannkorb with shoulders and a mask, flight holes: mouth and nostrils, 68×57 cm, second half of the 18th century, provenance: Timme’s farm in Hassel, district of Celle, now: Bomann-Museum Celle.

Bannkorb with a mask, flight holes: mouth (main), nostrils, and eyes, 44 × 39 cm, date unknown, previous ownership: unknown, now: Bomann-Museum Celle.

Bannkorb with a mask, flight holes: mouth (main) and nostrils, 46 × 37 cm, unknown, previous ownership: unknown, now: Bomann-Museum Celle.

Bannkorb with a front panel (oakwood), panel no longer in the original basket, flight hole: mouth, 53 × 42 cm, 1786, provenance: Küker farm, Nienhagen near Schwarmstedt, in Hans-Günther Brockmann’s private collection since 1965.

Bannkorb with a mask (oakwood), basket not original (woven by Bohm), flight hole: mouth, 51×43.5 cm, second half of the 19th century, prove- nance: Körker Beekeeping in Grethem, in Hans-Günther Brockmann’s private collection since around 1965.

Bannkorb with a mask, flight holes: mouth (main), eyes, and nostrils, 43 × 36 cm, second half of the 19th century, provenance: Wortmann’s apiary, Odeweg near Visselhövede, now: Hans-Günther Brockmann’s private collection.

Bannkorb with a mask, flight hole: mouth, 43×41 cm, date unknown, provenance: Martens’s farm, Kükenmoor, now: Hans-Günther Brockmann’s private collection.

Bann- korb with a mask, basket not original, flight holes: mouth (main), nostrils, and eyes, 43 × 40 cm, 1809, provenance: Hörmann’s farm, Bosse near Rethem, now: Hans-Günther Brockmann’s private collection.

Bannkorb with a mask, flight hole: mouth, 42×42 cm, 20th century, provenance: W. Heitmann’s apiary, Krelingen, now: Hans-Günther Brockmann’s private collection.

Bannkorb with a mask, flight holes: mouth (main), nostrils, and eyes, 40 × 42 cm, first half of the 20th century, provenance: W. Blanke’s apiary, Wihelmsdorf near Haste or Wunstorf, now: Hans-Günther Brockmann’s private collection.

Bannkorb with a mask, flight holes: mouth, nostrils, and eyes, 45×44 cm, second half of the 18th century, provenance: Wittmoor near Rethem, now: Hans-Günther Brockmann’s private collection.

Bannkorb with a mask (oakwood), flight holes: mouth, nostrils, and eyes, 46×41 cm, first half of the 19th century, provenance: Dreier’s farm, Otersen near Rethem, now: Hans-Günther Brockmann’s private collection.

Bannkorb with a mask, flight hole: mouth, nostrils, and eyes, 41 × 37 cm, 1901–20, provenance: Robert Knüdel’s apiary, Holm-Seppensen, now: Hans-Günther Brockmann’s private collection.

Bannkorb with a mask (similar mask in Historisches Museum Domherrenhaus Verden), flight hole: mouth, nostrils, and eyes, 39.5 × 43 cm, before 1950, provenance: W. Carstens’s apiary, in Hans-Günther Brockmann’s private collection since 1968.

Bannkorb with a mask, flight holes: mouth, 45 × 45 cm, first half of the 20th century, provenance: Hilmers’s farm, Barnbostel, now: Hans-Günther Brockmann’s private collection.

Bannkorb with a mask, flight holes: mouth, nostrils, and eyes, 44.5 × 44 cm, 20th century, provenance: Hilmers’s farm, Barnbostel, now: Hans-Günther Brockmann’s private collection.

Bannkorb with a mask, flight holes: mouth, nostrils, and eyes (not originally perforated), 44×40 cm, 1901–20, provenance: Brockmann’s apiary, Westenholz near Fallingbostel, now: Hans-Günther Brockmann’s private collection.

Bannkorb with a mask, flight holes: mouth and nostrils, 40 × 36.5 cm, date unknown, provenance: Gerd Bünger, Stellichte, now: Hans-Günther Brockmann’s private collection.

Bannkorb with a mask, flight holes: mouth (main), nostrils, and eyes, 37.5×40 cm, date unknown, provenance: Lüdermann’s apiary, Gross-Heins, now: Hans-Günther Brockmann’s private collection.

Bannkorb with a mask, flight holes: mouth, 38 × 37 cm, before 1951, provenance: Wesseloh’s apiary, Wehnsen, now: Hans-Günther Brockmann’s private collection.

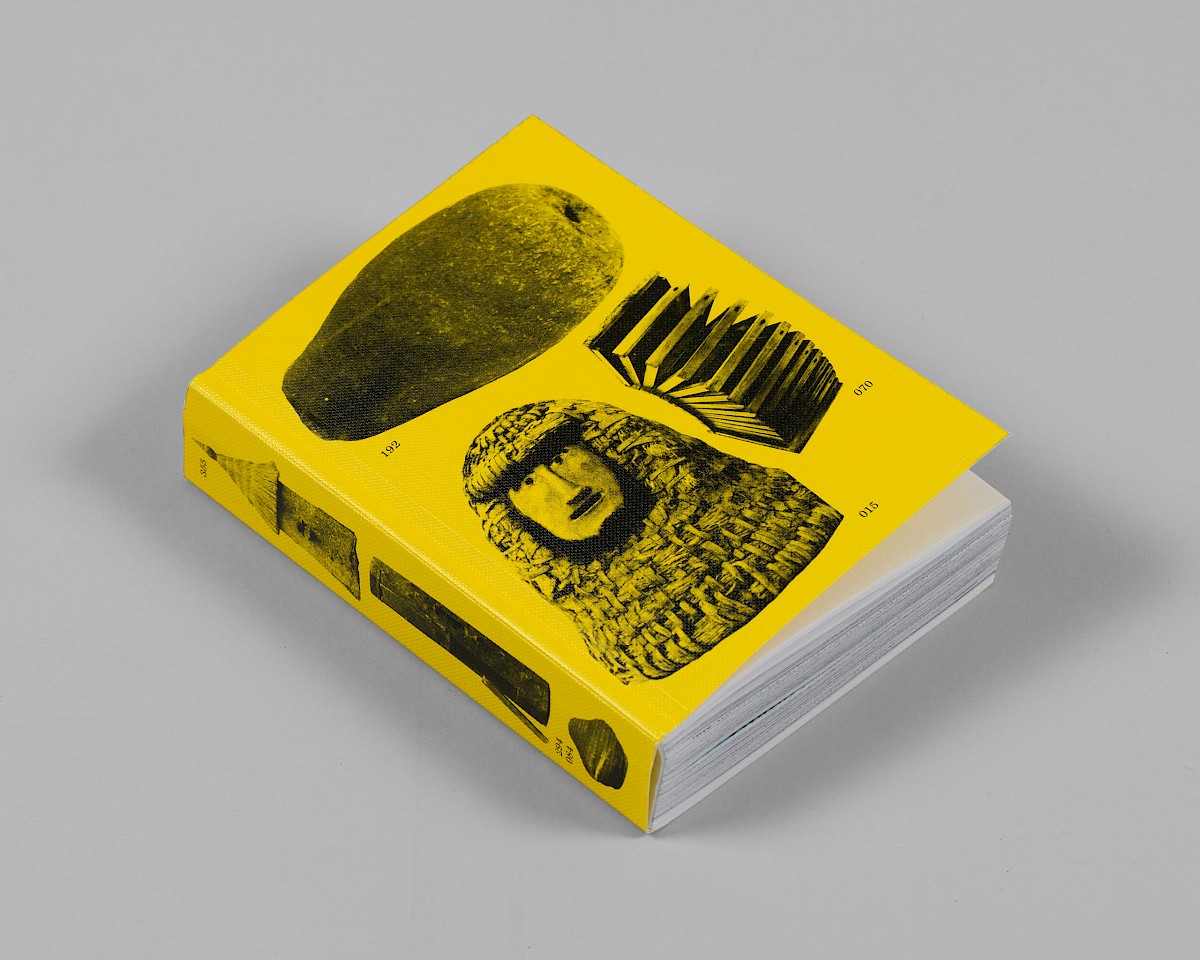

In 1852, the modern beehive was patented. Its subsequent success largely eliminated diversity in beehive design and led to the obsolescence of a varied history of alternative beekeeping techniques. Through an array of archival images, this book uncovers that forgotten history, offering a renewed perspective which challenges conventional historical linear narratives and creates a common ground for future beehive research.

Blurb by Apian (Ellen Lapper & Aladin Borioli)

448 pages, 109 (W) × 154 mm (H). The book was designed by Nicolas Polli and was printed in Switzerland in 2020. It also includes an essay co-written with Ellen Lapper.

The first edition was published in 2020 by RVB Books and Images Vevey, the second (2022) and the third (2023) by RVB Books, FR.

Folllow this link for info about Hives, 2400 B.C.E. – 1852 C.E.

Mikhail Bakhtin, Rabelais and His World (Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 1984)

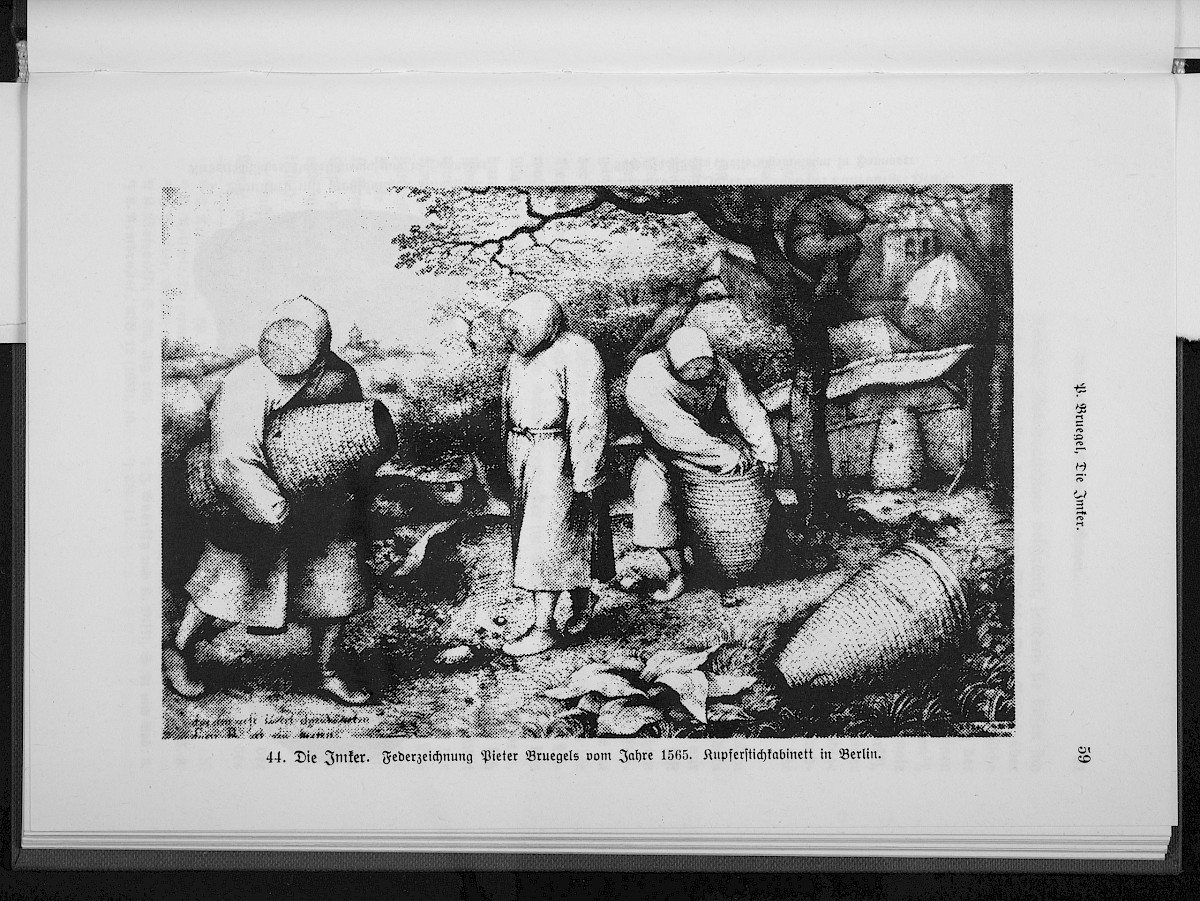

A reproduction of The Beekeepers and the Birdnester by Pieter Bruegel the Elder, circa 1568.

Source: Bruno Schier, Der Bienenstand in Mitteleuropa (Leipzig: S. Hirzel, 1939; repr. Wiesbaden: Sändig, 1979)

Bee Craft 59, no. 11. (November 1977)

Bee Craft 67, no. 07 ( July 1985)

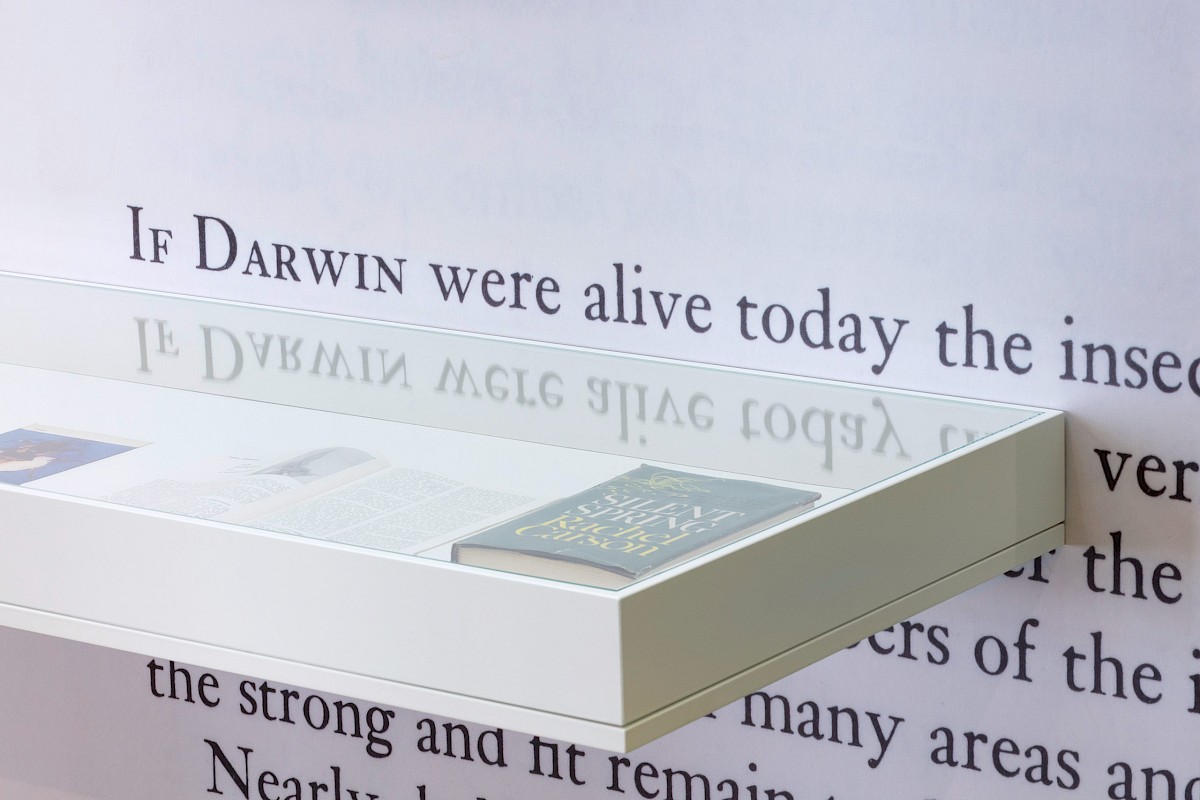

animal instinct / instinct animal – MBAL, Le Locle (Switzerland)

Installation views of Apian’s work as part of animal instinct / instinct animal group show in MBAL (Musée des Beaux-Arts du Locle, Suisse). The show ran from 14.10.2023 to 25.02.2024, and we showed a multimedia installation titled ‘05.CH.Drugs’. The installation explored the chronic exposure effects of neonicotinoids on bees, explicitly focusing on the impact of these pesticides on their brains.

For the installation, Apian collaborated with digital artist Nephila, visual anthropologist Ellen Lapper, and scholars Dr. Randolf Menzel (Freie Universität) and Dr. Mazi Sanda (University of Ngaoundéré).

Special thanks to curators Dr. Federica Chiocchetti and Séverine Cattin, and the entire MBAL team, especially Sulliane Bressoud, Caroline Bourrus, Fanny Blanc, and Martial Barret.

For more info, visit: https://www.mbal.ch/en/expo/animal-instinct-instinct-animal/

Image by Lucas Olivet.

Image by Lucas Olivet.

Image by Lucas Olivet.

Image by Lucas Olivet.

Queen Bees and the Hum of the Hive: An Overview of Feminist Hypertext’s Subversive Honeycombings

Using the aesthetic and metaphor of the beehive, Carolyn Guertin’s artwork – Queen Bees and the Hum of the Hive – weaves together a collection of hypertext essays about feminism and digital media theory. This artwork/essay/digital hive was first published in English in 1998 as part of the online journal BeeHive [Hypertext Hypermedia Journal].

You can access the artwork here: archive.the-next.eliterature.org/beehive/preserved/content_apps02/queen_bees/index.html

Screenshot, 2025, Firefox 141.0 (aarch64) on Mac OS Monterey Version 12.5

Screenshot, 2025, Firefox 141.0 (aarch64) on Mac OS Monterey Version 12.5

Screenshot, 2025, Firefox 141.0 (aarch64) on Mac OS Monterey Version 12.5

Directory of Cells in the Honeycomb:

The totality of the website was screenshotted (in August 2025) and is saved in The Ministry of Bees’s physical archive. In case the original website is down and you need to access a particular essay, please don’t hesitate to get in touch with us.

Following the feminist hypertext tradition, find the artwork also archived on the Cyberfeminism Index: https://cyberfeminismindex.com/#/queen-bees-and-the-hum-of-the-hive-an-overview-of-feminist-hypertexts-subversive-honeycombings

“The Beekeeper (Greek: Ο Μελισσοκόμος, translit. O Melissokomos) is a 1986 Greek drama film directed by Theodoros Angelopoulos. The film is the second installment in Angelopoulos’s “trilogy of silence”, preceded by Voyage to Cythera and followed by Landscape in the Mist. […] The film follows the journey of Spyros, a beekeeper, to various parts of Greece after his daughter’s wedding. Spyros has just retired as a teacher and sets out on his annual journey in spring to move his beehives to a series of locations with flowering plants. A girl hops on Spyros’s truck, and travels with him.” (Wikipedia 2025)

Film still (00:00:43)

Film still (01:53:50)

Film still (00:18:44)

Film still (00:32:45)

Film still (01:25:09)

Bees, Land & Liberation: a Conversation with Palestinian Beekeepers

“Bees, Land & Liberation: a Conversation with Palestinian Beekeepers” is a webinar series organised by Comb Cutters in partnership with the Union of Agriculture Work Committees (UAWC) and supported by Dream Defenders.

Discussions centre around the beekeeping and agriculture sector in Palestine, tackling the state of farming industries and food sovereignty. The event offers a place to connect beekeepers, agricultural workers, and environmental organisers who are taking seriously the question of land and food resources in Palestine.

Combcutters is a Beekeeping worker-owned co-op based in South Florida, US. They are committed to bee education and use bees as their medium to build a just and equitable world.

UAWC is the Union of Agricultural Work Committees in Palestine. They’re committed to protecting their land and supporting Palestinian farmers.

Dream Defenders is an organisation of young, influential Black and Brown people, organising towards a new vision for safety away from police and prisons and have been committed to a free Palestine since their inception.

The first iteration took place on 25th February 2024, and the second one on 12th July 2025.

Recordings of both events are available in English, Arabic, and Spanish. Here:

www.youtube.com/watch?v=KoJHI5TQ7FM&t=1405s (1st)

www.youtube.com/watch?v=U9QRh03hgxM&t=34s (2nd)

If the YouTube archive ends up missing, the English version was stored in The Ministry of Bees’ archive. Please don’t hesitate to contact us if you want to access it.

Pas de résultat